Reviewed by Beverly Slapin

Review Source: Teaching for Change

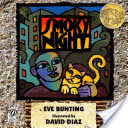

Book Author: Eve Bunting

On April 29, 1992, an almost all-white jury in the almost all-white suburb of Simi Valley acquitted four white Los Angeles Police Department officers of using assault and excessive force in the videotaped beating of a Black man named Rodney King. On the evening following the acquittal, massive violent public protests—“riots”—broke out, centered in South Central Los Angeles, a predominantly Black and Latino neighborhood. The Army, Marines, and National Guard were sent in to quell the rebellion, which lasted several days and resulted in many deaths, many fires, and much destruction. The media were all over it, focusing on the violence and looting, all but ignoring the causes.

When it was over, community activists and several studies spoke of continuing patterns of racism and police brutality, lack of educational opportunities, and widespread poverty and unemployment as root causes of the rebellion. In the end, little or nothing was done to address the underlying realities of poverty and despair in South Central.

What has come to be known as the “Rodney King riots” is the background for Eve Bunting’s picture book, Smoky Night.

In Smoky Night, this is the way that Mama explains the South Central rebellion to her young son:

People get angry. They want to smash and destroy. They don’t care anymore what’s right and wrong. . . . After a while it’s like a game.

And Daniel observes, “They look angry. But they look happy, too.” Here, a Black woman’s words to her young Black son about their own neighbors and community make the “rioters” out to be violent monsters who enjoy ripping apart their own neighborhood. This is not the perspective of a Black woman and a Black child in South Central; it’s the perspective of a white woman who appears to be exhibiting what Joyce King calls “dysconscious racism”—“perceptions, attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs that justif[y] inequality and exploitation by accepting the existing order of things as given. . . . [It’s] a form of racism that tacitly accepts dominant [w]hite norms and privileges.”

And Daniel observes, “They look angry. But they look happy, too.” Here, a Black woman’s words to her young Black son about their own neighbors and community make the “rioters” out to be violent monsters who enjoy ripping apart their own neighborhood. This is not the perspective of a Black woman and a Black child in South Central; it’s the perspective of a white woman who appears to be exhibiting what Joyce King calls “dysconscious racism”—“perceptions, attitudes, assumptions, and beliefs that justif[y] inequality and exploitation by accepting the existing order of things as given. . . . [It’s] a form of racism that tacitly accepts dominant [w]hite norms and privileges.”

Smoky Night led a young reader to remark in an Amazon.com review, “This is a story about a boy named Daniel. He lives in a bad neighborhood with lots of rioting.”

In 1995, Dan Hade gave a talk at a children’s literature conference. The talk was called “Aestheticizing the Poor/Anesthetizing the Reader: The ‘Social Justice’ Books of Eve Bunting.” In only 13 words, this is a perfect analysis of Bunting’s books. In Smoky Night, Bunting’s shallow portrayal of a complex event in a particular neighborhood trivializes both the neighborhood and the people who live in it, leading young readers who are not Black to see only a “bad neighborhood.”

To publish a children’s book about the South Central rebellion—and it can be done—would take a talented writer who understood the conditions that led to the rage that exploded in the aftermath of the acquittal of four white police officers who beat a Black man. This doesn’t mean that a children’s book has to be a sociological treatise—just that a book that is about a social issue should be honest in its description.

Rather, in Bunting’s trivialized interpretation of the South Central rebellion, there’s no racism, no poverty, no injustice—just angry people who enjoy looting and can take a lesson in getting along from a couple of cats.

By using the narrative voice of a young child who doesn’t understand why his neighborhood is exploding, Bunting evades having to explore complex social issues in any depth. In reality, this young child would know what’s going on; he would have experienced, in ways large and small, the anger and disillusionment in an economically disenfranchised community.

But in Bunting’s comfortable worldview, unfortunate things just happen, and some people—“those people”—just have to try harder to get along with one other.

All children begin to learn about their worlds at a very young age. They quickly soak up and internalize the values and cultural markers of their parents and communities. If children who are poor and marginalized continually see themselves reflected in books such as Smoky Night, the cognitive dissonance they absorb can lead to real socio-emotional problems. And if children who are not poor and marginalized—who are white and comfortably middle class, for instance—continually see children who are poor and marginalized as “other,” the racism they absorb can lead to real problems as well.

It doesn’t matter to this reviewer what Eve Bunting’s intentions are. And, yes, the South Central rebellion was violent and scary to everyone. But to moralize to poor and disenfranchised people about their individual responsibility to get along with each other—as Bunting has done in Smoky Night—is racist and obscene.

Beverly Slapin wrote Books without Bias: A Guide to Evaluating Children’s Literature for Handicapism and co-edited Through Indian Eyes: The Native Experience in Books for Children and A Broken Flute: The Native Experience in Books for Children. For many years, she was a children’s content editor for Multicultural Review, and was co-founder and executive director of Oyate.

Smoky Night by Eve Bunting

Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on 1999

Genres: Economic Class, Policing

Pages: 36

Reading Level: Grades 1-2

ISBN: 9780152018849

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Also by this author: Cheyenne Again

SYNOPSIS: Daniel and his mother look out their window at the smoky night below. There are looters on the street, fires in the distance. Daniel clutches his cat, Jasmine. But later, when they're forced to leave their apartment building, Jasmine can't be found.

Mrs. Kim's cat is missing, too. Where are they? They can't be with each other. Those cats don't get along...

"Smoky Night" is a story about cats - and people - who couldn't get along until a night of rioting brings them together.

Thank you for this thoughtful review. It gives me a perspective that I will pass on to my elementary teaching staff. This book is somewhat prized as multicultural fiction in my school district. I very much appreciate your thought process here.