Reviewed by Olvin Abrego Ayala

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Book Author: Andy Carter

Margarito’s Forest/El Bosque de Don Margarito is a nonfiction narrative that centers on the real-life legacy of Margarito Esteban Álvarez Velázquez, affectionately known as Don Margarito, a member of the K’iche’ community in the highlands of present-day Guatemala. A captivating intergenerational story, the book serves as an accessible introduction to kinship, Indigenous cosmovisions, environmental changes, and the poignant era of the Maya Genocide in Guatemala.

The story unfolds as a dialogue between Doña Guadalupe (María Guadalupe Velásquez Tum) and her grandson, Esteban, Don Margarito’s great-grandson. It explores the forest he nurtured during his lifetime and the enduring legacy it holds for the community. The book concludes on a hopeful yet grounded note, emphasizing the importance of preserving knowledge while acknowledging the ongoing struggles of Indigenous communities in Guatemala and alluding to the devastating impact of the climate crisis.

The book has the following themes of note.

Points of View

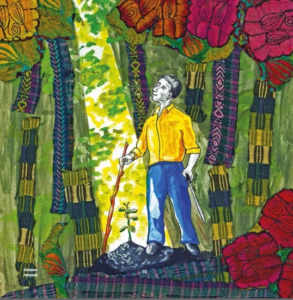

Despite being written by an outsider to the community (Andy Carter), the book primarily highlights the perspectives of the community members themselves. Unlike many works by outsiders where the communities are simply objects for consumption, this book approaches the subject differently. The project placed a strong emphasis on collaboration, with active involvement from community members. The book opens with a dedication to the local artists, storytellers, and true protagonists of the story: María Guadalupe Velásquez Tum, Virgilio Vicente, and the children of Saq Ja’ — who all played pivotal roles in its creation. Illustrator Allison Havens conducted workshops where the children of Saq Ja’ contributed drawings used in the book’s illustrations.

Despite being written by an outsider to the community (Andy Carter), the book primarily highlights the perspectives of the community members themselves. Unlike many works by outsiders where the communities are simply objects for consumption, this book approaches the subject differently. The project placed a strong emphasis on collaboration, with active involvement from community members. The book opens with a dedication to the local artists, storytellers, and true protagonists of the story: María Guadalupe Velásquez Tum, Virgilio Vicente, and the children of Saq Ja’ — who all played pivotal roles in its creation. Illustrator Allison Havens conducted workshops where the children of Saq Ja’ contributed drawings used in the book’s illustrations.

This, combined with the incorporation of oral histories, presents the community not just as subjects but as active participants in the narrative, and perhaps that’s why the story resonates so powerfully. While collaboration and attention to detail are commendable, they should be the norm. Another thing that the book does well is the inclusion of phrases in the K’iche’ language, which — although sometimes placed in awkward spots — aim to resonate with readers from the community. Not just this, but there are also English-K’iche’ and English-Mam versions, which decenter Spanish as the standard and make it one of the few books in those languages.

Maya Cosmovisions

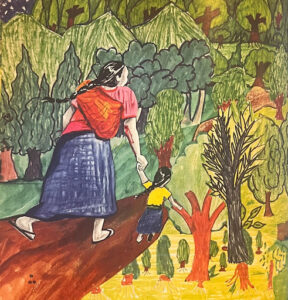

Central to the story’s themes are familial kinships and the passing down of knowledge from elders — the protectors of knowledge — through oral histories and active participation. The book also emphasizes the relationship with the land, centered around harmonious living. There is a point in the book where Don Margarito says, “This forest is my partnership with the land. Someday it will benefit my family and many others” (17). The emphasis on partnership is important, as he showcases mutual respect for the land and understands that they are part of the same territory. This follows the philosophy of many Indigenous communities (different cosmovisions, as they are not a monolith) and modern iterations like body-territory feminism, which Lorena Cabnal, a Guatemalan activist, subscribes to.

One reason this book resonates so much with me is because the farming system described on page 13 sounds like the farming system I grew up in in neighboring Honduras. Doña Guadalupe explains that the land was passed down to her father, Don Margarito, from his dad, and that he, along with the men in the village, work the land. She talks about how her dad would grow enough corn and beans to feed them, which sounds a lot like the subsistence farming system of Milpa from my childhood. This system is older than 7,000 years, predating the colonists. In a Milpa system, the people depend on the land to survive, which creates an important bond with it.

(Un)natural Disasters

The book also brings up a very important period in Guatemalan history. It directly references 1980s Guatemala, when the country was in the midst of an ongoing “war” often called the Maya Genocide, as many of the targeted people were Indigenous communities. This tumultuous history began after the U.S.-backed United Fruit Company (Chiquita Banana) 1954 coup d’état and ended with peace accords in 1996. The country’s military, backed by the U.S.-Israeli war machine, committed crimes against humanity under the leadership of Efraín Ríos Montt, a military war criminal. They employed scorched earth military tactics, which involved burning crops and means of subsistence to kill people. This is directly mentioned in Margarito’s Forest, all of which took place in the Saq Ja’ community during 1981 and 1982. In contrast to most children’s books on Central America, this book does not gloss over the horrors of this period. The pictures on pages 20 and 21 depict the killings and bloodshed of the community, whose ancestral knowledge and livelihoods were endangered. It is important to note that although the genocide was named during this period, the ongoing project began with the arrival of Spanish colonizers more than 500 years ago.

The book also brings up a very important period in Guatemalan history. It directly references 1980s Guatemala, when the country was in the midst of an ongoing “war” often called the Maya Genocide, as many of the targeted people were Indigenous communities. This tumultuous history began after the U.S.-backed United Fruit Company (Chiquita Banana) 1954 coup d’état and ended with peace accords in 1996. The country’s military, backed by the U.S.-Israeli war machine, committed crimes against humanity under the leadership of Efraín Ríos Montt, a military war criminal. They employed scorched earth military tactics, which involved burning crops and means of subsistence to kill people. This is directly mentioned in Margarito’s Forest, all of which took place in the Saq Ja’ community during 1981 and 1982. In contrast to most children’s books on Central America, this book does not gloss over the horrors of this period. The pictures on pages 20 and 21 depict the killings and bloodshed of the community, whose ancestral knowledge and livelihoods were endangered. It is important to note that although the genocide was named during this period, the ongoing project began with the arrival of Spanish colonizers more than 500 years ago.

In the “About” section of the book, the author briefly mentions climate change. This is important, as just as the war migrations of Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Nicaraguans were happening in the 1980s, intrinsically changing the fabric of United States demographics, climate migrants and refugees will continue to be an ongoing issue. Climate change is a global injustice. Countries in the Global South, which contribute the least to emissions, are the most impacted, especially due to limited resources for mitigation efforts. Guatemala is one of the hardest-hit countries by climate change. Its location in the Central America Dry Corridor (affected by El Niño), coupled with extreme weather phenomena and deforestation in the name of “development,” will continue to affect the country. The communities most impacted are those in rural, subsistence farming areas, similar to those depicted in the book. The ongoing issues of land access and sovereignty exacerbate the situation. In saying this, it’s important to recognize that for people in the Global South, climate change is not a distant threat but an existing and pressing reality.

Concluding Thoughts

Having read other Central American children’s books, I wish there were more of this caliber. We need books especially coming directly from Central American artists, storytellers, and others from all countries — Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Panama. These books should encompass our full identities, showcasing our culture and happiness just as much as they focus on our struggles.

The story in this book does not sensationalize the war nor depict its “characters” as perpetual victims, devoid of agency and true humanity. It ends on a positive note, highlighting the actions communities are taking in the present. I wish it explained the role of foreign intervention more extensively or even mentioned United Fruit Company’s involvement in the “About” section, but I understand that it can only do so much within the confines of a short picture book. Overall a great read, and a must in every school library.

Vocabulary

K’iche’: A Mayan language spoken by the Kʼicheʼ people of the central highlands in Guatemala. It is the second most widely-spoken language in the country with over 1 million speakers.

Milpa: The milpa is a traditional agricultural system in which maize is intercropped with other species. It has existed in Central America and parts of Southern Mexico for multiple millennia.

Cuerpo-Territorio: “The impossibility of separating the individual from the collective body as well as the body from its territory” and deliberalizes “the notion of body as individual property to instead focus on our interdependence.” (Verónica Gago)

Maya: The word “Maya” is used to describe the Maya civilization and other non-linguistic aspects of their culture.

Mayan: the word “Mayan” is used to describe the languages that are spoken by the Maya people.

Central America Dry Corridor: Central American region exposed to prolonged dry spells and unpredictable rainfall, a phenomenon exasperated by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation system.

United Fruit Company: Currently named Chiquita, an American multinational corporation that once owned around half of Guatemala’s arable land and directly participated in the 1954 coup.

Additional Resource

For more information on the Indigenous languages of the Maya, read about The Maya Book Project.

Olvin Abrego Ayala interned with Teaching for Change during the summer of 2024. Salvadoran-born and Honduran-raised, he is an undergraduate student at Dartmouth College majoring in Latin American, Latinx, and Caribbean Studies with a focus on Central American Studies. He co-leads his school’s first Central American Club, CAUSA, and is a student researcher for the Central America Project.

See another review of Margarito’s Forest / El Bosque de don Margarito by Latinos in Kid Lit.

Find more recommended titles on our Central America booklist.

Margarito's Forest English-K'Iche by Andy Carter

Published by Hard Ball Press on April 15, 2016

Genres: Central America, Environment

Pages: 42

Reading Level: Grade K, Grades 1-2, Grades 3-5

ISBN: 9798985097979

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Also by this author: Bosque de Don Margarito

Publisher's Synopsis: Margarito's Forest is a story of Maya culture and wisdom passed from one generation to the next. This beautifully illustrated bilingual book in English and Spanish, with excerpts in K'iche', is based on María Guadalupe's memories of her father, Don Margarito Esteban Álvarez Velázquez.

Leave a Reply