Reviewed by Paige Pagan

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Book Author: Bernard Waber

Lovable Lyle is the fourth picture book in a series about Lyle the Crocodile who lives with the Primm family. In this book, Lyle is confronted with an enemy, the new girl in town, Clover Sue Hipple, who keeps leaving him threatening letters much to the surprise of the Primm family who assumes everyone loves Lyle. The Primms determine that the only way to resolve the situation is for Lyle to win over the affection of Mrs. Hipple, who doesn’t allow Clover to play with crocodiles. Published in 1969, this book reflects the segregationist ideals upheld in society at the time. Lyle is tokenized, burdened by the responsibility of proving his exceptionalism to those around him. The Primms teach Lyle that the method to combat discrimination is through assimilation, providing children with the misconception that people will only like you if you are similar to or act like them. Other themes included, but not explored in depth in this book, are vandalism and arrest.

Mrs. Hipple disapproves of “a crocodile living amongst decent, respectable people” (p. 27) and passes along the mentality that crocodiles are by nature inferior to Clover. Because Lyle is loved and played with by all the other children, Clover finds herself often left out, causing an even stronger hatred towards Lyle to fester. In her letters to Lyle she says, “I hate you so much I can’t stand it” (p. 8) and “I wish you would go away and never come back” (p. 20). The Primm’s question, “Whatever reason could anyone have for hating Lyle?” (p. 8). Lyle is discriminated against for being an animal intruding into the human world where he doesn’t belong. The Primms tell Lyle to be himself and in that way, he will show the Hipples that he is likeable. As a result, Lyle works to overcompensate for any flaws he may have by being friendly, helpful, entertaining, and generous. Lyle works so hard at being nice that he eventually collapses from exhaustion.

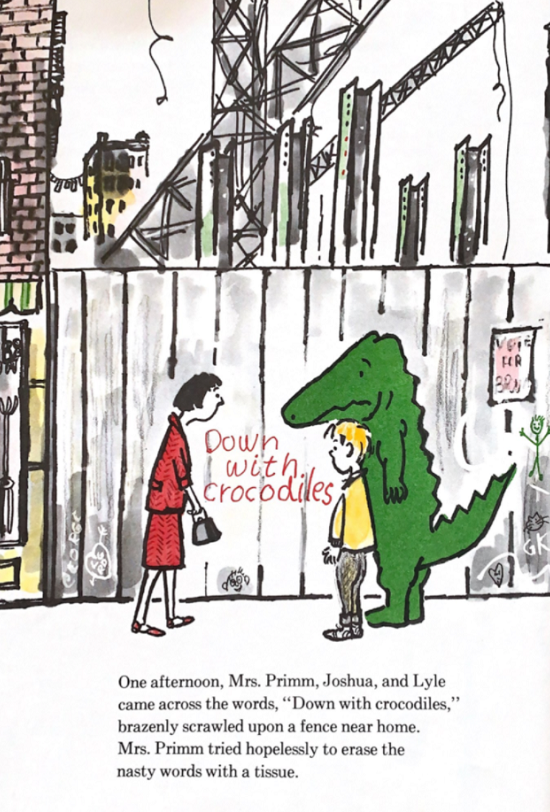

Despite all these efforts, the Primms come across a vandalized fence that reads in bright red letters: “Down with crocodiles” (p. 18).

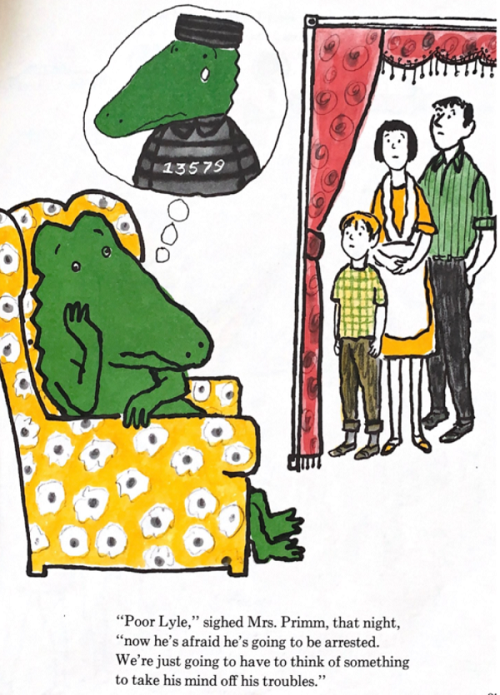

Instead of teaching Lyle that hatred is a result of others’ feelings of privilege and superiority and not by any fault of his own, Mrs. Primm attempts to erase the hate slur with tissue to no avail. Mrs. Primm also neglects to reassure Lyle that he is an equal, perhaps because that would include denouncing her own privileged position as a human. While the Primms are sympathetic towards Lyle, they are not active in seeking out change in this segregationist society. Mrs. Primm even invites Mrs. Hipple over to show her that Lyle has “the very best manners” (p. 28). She doesn’t consider the vulnerable position this invitation would put Lyle in and is surprised when Lyle hides in fear once Mrs. Hipple arrives. Lyle’s protection is not prioritized and instead he is expected to fulfill the seemingly impossible task of showing his enemy why her judgement is incorrect. When Mrs. Hipple discovers Lyle hiding in the closet, she threatens to have him arrested. In this instance, Lyle’s own home transforms from a sanctuary into an unsafe space. Lyle is shown crying over the prospect of his arrest while the rest of the Primms watch him blankly.

The Primms neither come to Lyle’s defense against Mrs. Hipple, nor confirm that they will not allow him to get arrested for no reason. They believe that if they take Lyle to the beach, his favorite place, it will ease “his troubles” (p. 27). Because the Primms cannot relate to Lyle’s troubles, they decide to ignore them.

When Mrs. Hipple sees Lyle at the beach, she reminds the lifeguards that no crocodiles are allowed. On their way to tell Lyle to leave, Mrs. Hipple and the lifeguards see Clover drowning. All of the onlookers exclaim that there’s a crocodile moving towards Clover, but Mrs. Primm shouts, “It’s Lyle the Crocodile!” (p. 45) exasperating the “one only” message. Lyle must remain separate from the rest of the crocodiles to maintain his exceptionalism, which entails being like the humans around him and even going beyond their abilities. When Lyle saves Clover before the lifeguards can, he becomes the hero and Mrs. Hipple realizes that he is good after all and permits Clover to play with him. Lyle has to work twice as hard as humans to be recognized and validated.

Even though the book ends with the message that people can change, it should not have been Lyle’s sole responsibility to change them. In the 1960’s civil rights era in America, there were leaders being assassinated for speaking out against the ideas taught in this book. In much the same way, Lyle can be likened to people of color (POC) who were segregated and discriminated against and are still to this day. Lyle was a target for existing while being a crocodile, similar to how POC are targets for existing while not being white. The remedy to hate is not assimilation and tolerance, but through teaching that being authentically yourself should always be enough. I do not recommend this book for children and if it is taught, I encourage adults to use it to initiate conversations about why discrimination and tokenism are problematic and why there is a need for antiracism and self-love.

Paige Pagan is a Social Justice Books program specialist at Teaching for Change.

Lovable Lyle by Bernard Waber

Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on 1977-04

Genres: Racial Identity, Racism

Pages: 48

Reading Level: Grade K

ISBN: 9780395253786

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Publisher's Synopsis: Lyle is distraught to learn he has an enemy and tries to be an even more lovable crocodile than he was before. "Patterned in the same format as its successful predecessors, this book has color illustrations that are as delightfully revealing of Lyle & Co. as ever." — School Library Journal

Leave a Reply