The third graders huddled around the photographs, their faces filled with concern. “Whoa, that’s a lot of bags,” Sam said, scooting closer to examine a picture of a goat surrounded by towering mounds of twisted, multicolored plastic bags.

“Oh no!” Claire exclaimed. “It looks like that goat is going to eat the plastic.”

“Yeah, that’s crazy!” Eric leaned in to gaze at the photograph. “How did all of those plastic bags get there? Someone needs to clean them up.”

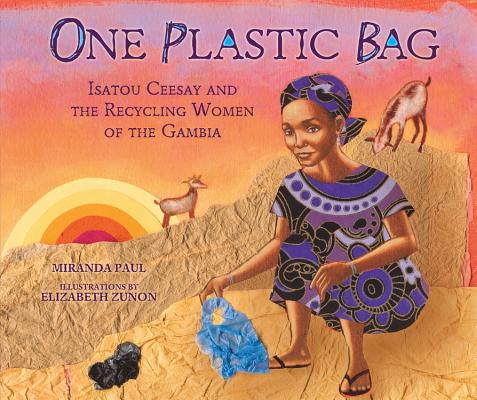

“Eric, I’m so glad you said that. I can tell that you’re really going to enjoy the story I’m going to read to you today. It’s called One Plastic Bag, and it’s the story of a woman named Isatou Ceesay. She saw all of those plastic bags and thought the same thing you did: someone needs to clean that up! Let’s read about her.”

The buzz in the classroom quieted down as I began to read. One Plastic Bag by Miranda Paul tells the true story of Isatou Ceesay and the Recycling Women of the Gambia. When the book opens, students meet Ceesay, then a child, as she carries a plastic bag home from the market. As I read, the students watched Ceesay grow into an adult who recognized the problems plastic bags caused in her village and decided to do something to help. Ceesay and other women in her village of Njau began to crochet coin purses made from the plastic bags, an effort that gives the women their name: the Recycling Women of the Gambia. The ending of One Plastic Bag looks into the future, predicting a time when the village is beautiful and free of trash. The students listened attentively, hooked to the story.

As an early childhood science and math specialist, I often struggle to find authentic ways to address issues of social justice in my classroom. There are few resources aimed at teaching about environmental justice, climate change, and activism in the early childhood years. Those resources that do exist typically fall into two groups: they are either very simplistic and focused almost exclusively on individual actions, or they cover scientific content that is far too advanced for young learners. For these reasons, my work with young children up until this point often focused on individual actions like recycling: it was clear, concrete, and had a definite outcome. In that vein, I had recently organized a school-wide study of recycling, and the third graders took the lead on teaching the younger children what could be recycled. They relished this leadership role and were primed to think about how the work they had just done within the school could connect to organizing and activism on a larger scale.

It was clear to me right away that One Plastic Bag would make a great conclusion to our unit study of recycling and community organizing. My students relished “true stories,” and I loved how the book centered collective action: a group of women who were activists within their community. The ending, though, just didn’t feel right.

Just a week before, during a meeting of the Anti-Bias Early Childhood Working Group organized by D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice, my colleagues and I discussed how organizing and activism are portrayed in picture books. After reviewing a slew of picture books, we noted that many books about organizing and activism written for children often have neat, tidy endings that fail to acknowledge the ongoing work of activism. What messages were we sending children with such endings, we wondered? How could we, as teachers and activist ourselves, help children consider the realities of activism?

By its very nature, activism is hard, grinding work. There are victories to celebrate, but there are more (arguably, many more) moments where activists must push through disappointments and failure. Were children’s books that ended “happily ever after” masking this reality? If they were, how could we help children see it?

One Plastic Bag too fell short in this regard: the women “dreamed that one day their village would be beautiful…and it was.” When I read the book aloud to my students, I wanted the children to interrogate the reality of such an ending and learn to ask questions about the process of creating lasting change. Is the village truly beautiful, or do the women need to continue their work? Do they face challenges along the way? Do people continue to discard plastic bags?

With these goals in mind, I launched the discussion with a simple question: “How does the ending of this story make you feel?”

“Amazing!” Carrie exclaimed before I could even finish the question.

“Happy!” said Noah, nodding. There were nods and a chorus of “Yeah, happy!”

“Well, I kind of knew…I felt relief that it ended happily, but I sort of knew because it’s about recycling women, and everyone’s recycling today,” said Carrie.

Morgan looked skeptical. “I”m a little happy and a little sad because it’s not really like that today.”

I looked around the classroom, gauging the expressions on the other children’s faces. I had hoped that such a comment would come up, but I was surprised at how organically it arose in the discussion. “I want to pause on that. Can you say a bit more about that — ‘It’s not like that today’?”

She hesitated, presenting her idea carefully. “Well, like…it’s better, but…we still have a lot of that.”

“Yeah,” Carrie chimed in, quick to abandon her previous position.

I tried to draw Morgan out. “Say more — there’s still a lot of what?”

“People throwing bags on the ground and not recycling.”

Sam nodded. “Well, I feel a little better, like good, because my dad went to a place and he got a plastic bag and it said made out of recyclables. And a lot of stuff, like the Crayola box, says its recycled.”

“Yeah, I’m thinking that a lot of people are getting into the recycling spirit because I heard that some companies are trying to make all of the bags out of recycled materials,” Alex agreed.

“I’m curious about something,” said Claire. “Because, I mean, there are going to be more plastic bags, so do they keep working on it, or…?” Her voice trailed off.

Yet again, I was stunned by how naturally the students came to the same question that my colleagues and I had. “That’s the same question I had, and it relates to what everyone said. I’m feeling good that the people in Njau are trying to get rid of a lot of plastic bags, but I’m wondering if the ending of the book.”

Jon jumped in. “Maybe that only happened for one year or something.”

“Okay,” I continued. “So do you think the plastic bags are still a problem?”

There was hubbub and a mixed response. Some children loudly called out “Yes!” Others said “no” more slowly and thoughtfully.

“Here’s the question that I want to pose to you: what do you think happens after this story ends? I think we agree that the ending ‘They wanted it to be perfect, and it was’ probably isn’t how it ended. I know you are writers in this classroom, so here’s what I want you to do. I want you to put all of these great thoughts down on paper. What do you think really happened to the Recycling Women?”

I paused there, not wanting to influence students’ thinking too much. The children hurried back to their desks and began writing. When I collected their responses, I saw a range of different ideas. Some children wrote that the people were happy because they cleaned up the plastic bags and made the village beautiful. Other took a more pessimistic approach, writing that plastic bags were still a big problem, and people eventually stopped cleaning them up.

A few responses, though, stood out. One said, “I think they’re going to keep doing it, but there gets to be more plastic, and they keep doing it, and there gets to be more plastic, so they keep doing it.”

The second said, “I think the women like to make the purses, so they keep making them. The purses are good because they clean up the plastic but also they make the women happy.”

When I read these responses, I smiled. Perhaps this discussion had planted the seed of authentic activism after all. Like activists everywhere, I celebrated this small victory with the knowledge that there was much work yet to be done.

Colleen Massaquoi has been a teacher for 10 years. She received her M.A.T. in Elementary STEM Education and specializes in teaching young children with diverse learning needs. She is currently the Math and Science Specialist at Concord Hill School, where she teaches children 3 years old through third grade. Colleen is a member of the D.C. Area Educators for Social Justice (DCAESJ) Anti-bias Education Working Group.

Leave a Reply