Edited by Keith Warner, Catherine Sunshine

Table of Contents | About the Editors | Reviews

Description

An incredible, informative collection of essays, oral histories, poetry, fiction, analysis, interviews, primary documents, beautifully illustrated timelines and maps and interactive & interdisciplinary teaching aids on the history, politics, and culture of the Caribbean, as it exists within the U.S. today.

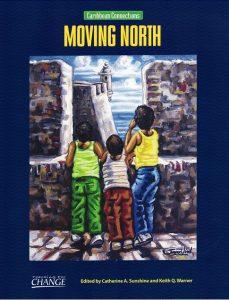

Migration from the Caribbean is reshaping the cultural landscape of many American communities. Moving North explores this process through fiction, poetry, personal narratives and interviews by women and men of Caribbean background living in the United States.

Some came to this country from the Caribbean as adults, while others arrived as children or were born here to parents from the Caribbean. Tracing their roots to Puerto Rico, the English-speaking West Indies, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Haiti, the writers in Moving North bring to life the migration experience and the contributions of Caribbean people to U.S. society today.

As with all the Teaching for Change publications, Moving North is packed with information for the educator, and those wishing an education, alike.

(Also see collection of readings on the Dominican Republic, English and Spanish editions.)

ISBN: 9781878554123

Publisher: Teaching for Change

Publication Date: September 1, 1998

Pages: 240

Language: English

Paperback Edition

About the Editors

Catherine A. Sunshine

Catherine A. Sunshine is a writer, editor and translator in Washington, D.C. She edited the previous titles in the Caribbean Connections series: Puerto Rico (1990), Jamaica (1991), and Overview of Regional History (1991). She is the author of The Caribbean: Survival, Struggle and Sovereignty (EPICA/South End Press, 1985, 1988), an introduction to Caribbean history and politics.

Keith Q. Warner

Keith Q. Warner is professor emeritus of French at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. Born in Trinidad and Tobago, he previously taught at the University of the West Indies and at Howard University. He is the author of Kaiso! The Trinidad Calypso (Three Continents Press, 1982); And I’ll Tell You No Lies (Calaloux Publications, 1993); and On Location: Cinema and Film in the Anglophone Caribbean (Macmillan, 2000).

Book Review

Review by Herman Hall, Everybody's Magazine, November 1998

For most of this century, Caribbean historians and writers focused their research primarily on relations between the Caribbean and Europe. A cardinal reason for this custom is that each Caribbean state was a colony of a Western European power and although formal constitutional links are almost eliminated, quasi-political, socio-economic, and cultural affiliations are maintained. Thus, there still exist a wealth of data for scholars to feast on.

The few researchers who concentrated on Caribbean and United States relations presented their work in formal intellectual and academic style and the average person did not find these books to be reader-friendly. Within the last decade more writers have been presenting books on Caribbean and United States relations which have been easier reading such as The Other Americans: How Immigrants Renew Our Country, Our Economy And Our Value by Joel Millman. The latest is Caribbean Connections: Moving North edited by Catherine A. Sunshine and Keith Q. Warner.

Caribbean Connections: Moving North is easy to read, informative, and entertaining. It is a text book that can be used in junior high schools and colleges in history, sociology, political science, literature and immigration classes. Caribbean Connections: Moving North is leisure reading.

Like a newspaper, magazine or novel, it can be enjoyed by straphangers (subway riders).

Every Caribbean man and woman knows that the region once belonged to various European powers but not many are aware of the indirect grasp and control the United States had and still has on the region. In layman's language, Moving North shows how United States national security policies, created as early as the 19th century, enabled the U.S. to dominate the region and why, as a result, countries such as Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba have not enjoyed political and economic stability.

During the Cold War, it was easy to say that the U.S. intervened in Haiti, Cubak and The Dominican Republic to curb the growth of communism. Today, as scholars study U.S. and Caribbean relations, it is clearly revealed that the U.S. forced upon the people evil and corrupt dictators such as the Papa Docs in Haiti, and Joaquin Balaguer and Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic.

In the old days when the U.S. invaded a country or its giant corporations established businesses there, a sizeable amount of the population was encouraged to emigrate to the United States. Small land owners were forced to sell their property for use as plantations and hotel resorts. Therefore, the former land owners had little choice but to travel to the United States in search of employment and a new life. Moving North explains why the emigrants left their shores for the U.S. and why distinct Cuban, West Indian, Haitian, Dominican, and other Caribbean communities can be found in urban areas across the U.S.

Two enjoyable and sometimes humorous parts of Moving North are "Life Stories and Caribbean Crossroads." Caribbean immigrants of all ages, backgrounds, and languages chatted about their experiences. E. Leopold Edwards' (a Jamaican immigrant who arrived in 1948) story was both humorous and informative. Miguelina Sosa and Jean Desir, immigrants from the Dominican Republic and Haiti, respectively, gave touching accounts of their experience. "Life Stories" corroborates the Caribbean-American saying, "all ah we are one." The stories revealed that whether the immigrant came from Haiti or Barbados, the Dominican Republic or Cuba, he or she encountered similar trials and tribulations on arrival in the U.S. Listeners of Von Martin's radio program in the Washington, D.C. and Maryland areas may find his interview refreshing.

When the 1990s in the U.S. is assessed, it would be revealed that it was a decade of anti-immigrant expression. It started in California as a measure to curb aid given to Mexican immigrants but the anti-immigrant sentiment quickly swept across the nation climaxing with the Republican-led U.S. Congress creating anti-immigration legislation. Moving North reveals the double standard practiced by U.S. immigration and right wing policy makers.

The U.S. in its futile effort to overthrow Fidel Castro at one time encouraged Cubans to emigrate to the U.S. by any means necessary. Thousands came. At the same time, states Moving North, "In 1981, under an agreement with the Duvalier government, the Reagan Administration ordered the Coast Guard to seize boatloads of Haitians at sea and return them to Haiti by force . . . 23,000 boat people were intercepted. Of these, 11 were admitted to the United States; the rest were forcibly repatriated without ever getting the chance to apply for asylum."

Moving North also reveals that Haitian immigrants, especially their children, have not been treated equally by other Caribbean immigrants. That's quite accurate. Last month, a Haitian-American in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn ran for a seat in the New York State Assembly. He won the endorsement of the New York Times but voters in the district, mainly English speaking immigrants, voted for the incumbent, a Jewish lady, whom the English-speaking West Indians say don't provide visible leadership.

What makes Caribbean Connections: Moving North so lively is that it has topics for everybody. For the person who has no interest in United States and Caribbean politics, economic and military relations, there is the section, "Fiction, Memoirs and Poetry." There one will find works from distinguished Caribbean and Caribbean-American poets and authors including former Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, Paule Marshall, Roy S. Bryce-Laporte, and Edwidge Danticat. Like other recent books on Caribbean immigrants in the U.S., Moving North includes people from the English-speaking Caribbean. It provides the customary historical overview of early West Indian immigrants and how they made a difference, such as Marcus Garvey and Claude McKay who was part of the cultural awareness in the 1920s and 1930s in Harlem, popularly known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Unfortunately, as most other authors, the editors of Moving North also made the mistake of over exaggerating the West Indian-American contribution. Today's English-speaking Caribbean immigrants live on the laurels of early immigrants. Today's immigrant is brilliant in organizing cultural events especially carnival and creating mom and pop businesses that mainly serve the immediate community. Yet, there is no central organization to create a distinct voting bloc and to speak with a single voice.

It is easy to make this criticism but it is difficult to solve this apparent weakness. Moving North points out, "West Indian-Americans may identify with African-Americans when practical but choose to emphasize their Caribbean heritage at other times." Here lies the root of the problem. Most children of West Indian-American immigrants identify with the African-American community and by the time they become adults are not motivated to join or strengthen institutions that their parents created. Therefore, West Indian-American organizations are temporary. They only serve one generation and then become defunct or ineffective. A new wave of immigrant arrives and the cycle is repeated.

Annual Caribbean-American carnivals provide the setting to show an example of this problem. On carnival day prominent African-Americans mainly in the Northeast who normally demonstrate no interest in Caribbean-American neighborhoods, concerns, needs and problems suddenly get on television to reveal that their parents and grandparents came from the islands.

Moving North effectively explains how immigrants from the English-speaking Caribbean were helped by the landmark 1965 U.S. Immigration law and how the achievement of Independence of their respective countries in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s further enabled them to emigrate. The Immigration Act of 1965 made it possible for families to be reunited and for women to enter the U.S. to do domestic work. The achievement of Independence made it possible for each new nation eligible to send a given number of nationals to the U.S.

As a result of nationhood and the 1965 U.S. Immigration Law, English-speaking West Indians flooded the U.S. for mainly economic and educational reasons. On the other hand, immigrants from Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Cuba came for mainly political and humanitarian reasons.

If Caribbean parents wish to explain to their American-born children why they came to America, Caribbean Connections: Moving North can be of tremendous help.