![]()

Reviewed by Deborah Menkart

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Book Author: Sarah Warren

Stacey Abrams is one of the most strategic, visionary, and dedicated political leaders of this century, so we were delighted to learn that there was a picture book for young children about her life.

Sadly, the book fails to do justice to her life. We know that books for young children cannot be overly detailed and need to be sensitive to the developmental stages of the readers. However, this book goes overboard in generalizations, in not naming the oppression she faced, and in presenting her life devoid of the long history of voting rights activism in Georgia and in her family.

There have been many recent critiques of how Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela, and other leaders are placed on a pedestal as if they alone made or led the movement. The subtext is that young people need to wait for another hero like them to come along and save us. This book about Stacey Abrams falls into the same trap. Young readers would have no idea that there is a long history of organizing in Georgia that Abrams tapped into — nor that her work was part of and in collaboration with organizations led largely by African American women.

The book is so general in its descriptions that it might pass the right wing filters that flag books for honest discussions of racism and resistance.

Race is barely mentioned and organizations are left out entirely. It is all about Stacey Abrams as a heroic individual who must not see race since she never mentions it.

Here are some examples of our concerns.

Long Tradition of Organizing Is Absent

The text says,

Stacey was the first Black woman to hold the job. She had her own way of doing things: She listened. She learned. She agitated and collaborated.

This implies doing things one’s own way, as if you are the first, a maverick alone, is better. This would have been a time to say that she drew on a long tradition of Black leaders in Georgia, dating back to Reconstruction, who faced adversity in their role — like Henry McNeal Turner and Julian Bond. That is all one would need to say for young people to know she stood on shoulders, she did not walk alone.

Charity Over Civic Activism

The picture book features Stacey serving food at a soup kitchen. A worthwhile activity and likely one she did — but it does not challenge the status quo. According to the National Women’s History Museum, Stacey’s parents were activists and “advocated civic engagement. Family outings to the polls and outreach trips to prisons were frequent.”

The picture book features Stacey serving food at a soup kitchen. A worthwhile activity and likely one she did — but it does not challenge the status quo. According to the National Women’s History Museum, Stacey’s parents were activists and “advocated civic engagement. Family outings to the polls and outreach trips to prisons were frequent.”

Why were one of those activities not featured? It is already the case that too few children’s books include any reference to prisons despite the fact that countless students have family members who are imprisoned and prisoners are such a large portion of the U.S. population.

In addition, Abrams’ life has been that of an organizer — a tradition that is often denigrated in mainstream culture. (For example, Barack Obama was critiqued by the right during his campaign for having been an “organizer” in Chicago. Serving soup would not have been fodder for attack ads.) Why emphasize charity over civic engagement and resistance?

Colorblind

The book frequently side steps any mention of race, even when racism is central to the story. For example:

School

The text says,

The law said Stacey has the right to an equal education, but some schools got more support than others. . . .

It should say something like,

. . . white schools got more support than schools for African American, Latino, and Native American children.

– or –

. . . schools with white students got more resources than those with children of color.

The text goes on to say,

None of the other kids looked like Stacey.

That assumes skin color is an all-encompassing characteristic. It should say “Stacey was the only Black student” or “Stacey was one of few Black students” — whichever was the case. Children need to hear adults feeling comfortable naming and discussing race.

Governor’s mansion

The text says about her trip to the Governor’s mansion,

. . . but the guard wouldn’t let her family in.

It should say,

. . . but the white guard wouldn’t let her family in.

Disenfranchised voters

The text says,

Some Georgians had been treated as if they did not matter. But they mattered to Stacey.

The word “some” understates the scale of disenfranchisement. Again, what is wrong with saying Black? It should say,

Tens of thousands of African Americans, Latinos, and immigrants had been treated as if. . .

Police officers

The text says,

. . . in Los Angeles, California, police officers were caught on camera beating a Black man named Rodney King.

Why not identify the race of the officers since the race of the victim is identified?

People and Organizations Are Nameless

By naming very few people other than Stacey Abrams, it places Abrams on a pedestal. For example:

Mayor

The text says,

. . . where she saw how the mayor, the first Black man to lead Atlanta. . .

It would be better to name Maynard Jackson. It would not overly complicate the story and clarify that other people played a role in this history.

Organizations

The text says, “volunteers asked” as if they were all random individuals. The book could have named some of the groups that came together such as Black Voters Matter, MiGente, New Georgia Project, Fair Fight. These are all group names that young people can understand. Again, if we never mention organizing and organizations, then they are seen as dangerous or less heroic. For example, we are told that Rosa Parks’ stance on the bus was to be admired because it was spontaneous. Her trip to the Highlander Center to study organizing is seldom mentioned in children’s books and at the time led her to be labeled as a communist and agitator.

Ambiguous Conclusion

The text says,

Hundreds of thousands of first-time Georgia voters helped pick the people who would lead everyone into the future. . . The people had power.

What power is being referred to? She lost. Or is it Raphael Warnock’s victory? That would need to be said.

Timeline Falls Short

A timeline on U. S. voting laws in a children’s book cannot include every event. But this one leaves out two of the most significant events and organizations in the history of voting rights in Georgia. There is no mention of Reconstruction (although two Reconstruction amendments are listed), nor the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) with its headquarters in Atlanta.

Back Cover Message

The statement “Every Voice Matters” on the back cover sounds like one more attempt to pass the anti-CRT filters. It is an “All Lives Matter” refrain. It would be better to state “Black Lives Matter” or “Voting Rights for All.”

We hope all or at least some of these issues can be addressed in a subsequent printing of the book. Many would just take a few word changes. The result would be young people learning lessons from Stacey Abrams’ life that they can apply to their own about what racism looks like and how to organize for justice.

Deborah Menkart is executive director at Teaching for Change.

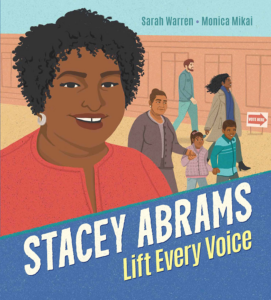

Stacey Abrams by Sarah Warren

Published by Lee & Low Books on 2022

Genres: Biography and Autobiography

Pages: 40

Reading Level: Grade K, Grades 1-2, Grades 3-5

ISBN: 9781643794976

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Stacey Abrams is the daughter of two civil-rights activists. She loved going into the voting booth with her parents on Election Day, knowing that their voices mattered. She loved school, even when she was the only Black student in her gifted classes. She loved her classmates at Spelman College — a historically Black institution — and worked hard to see they received the fair treatment they deserved.

And today, she brings all those experiences to her role as politician, author, and voting-rights advocate, helping to ensure that every person has a say and every vote gets counted. Stacey Abrams: Lift Every Voice follows Stacey's life from her girlhood to the present, but it also portrays the ordinary people that Stacey fights for — the beautiful and diverse America that shows up to stand with one another. Backmatter includes a timeline of changes in US voting rights law from the Constitution through the present day, demonstrating both how far the country has come and how far we have to go. With its spirited text and vivid illustrations, Stacey Abrams: Lift Every Voice will inspire readers to take their own steps forward.

Leave a Reply