On December 15, 2018, Teaching for Change joined an important dialogue about representation in children’s literature on-stage at the Oprah Winfrey Theater in the National Museum for African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

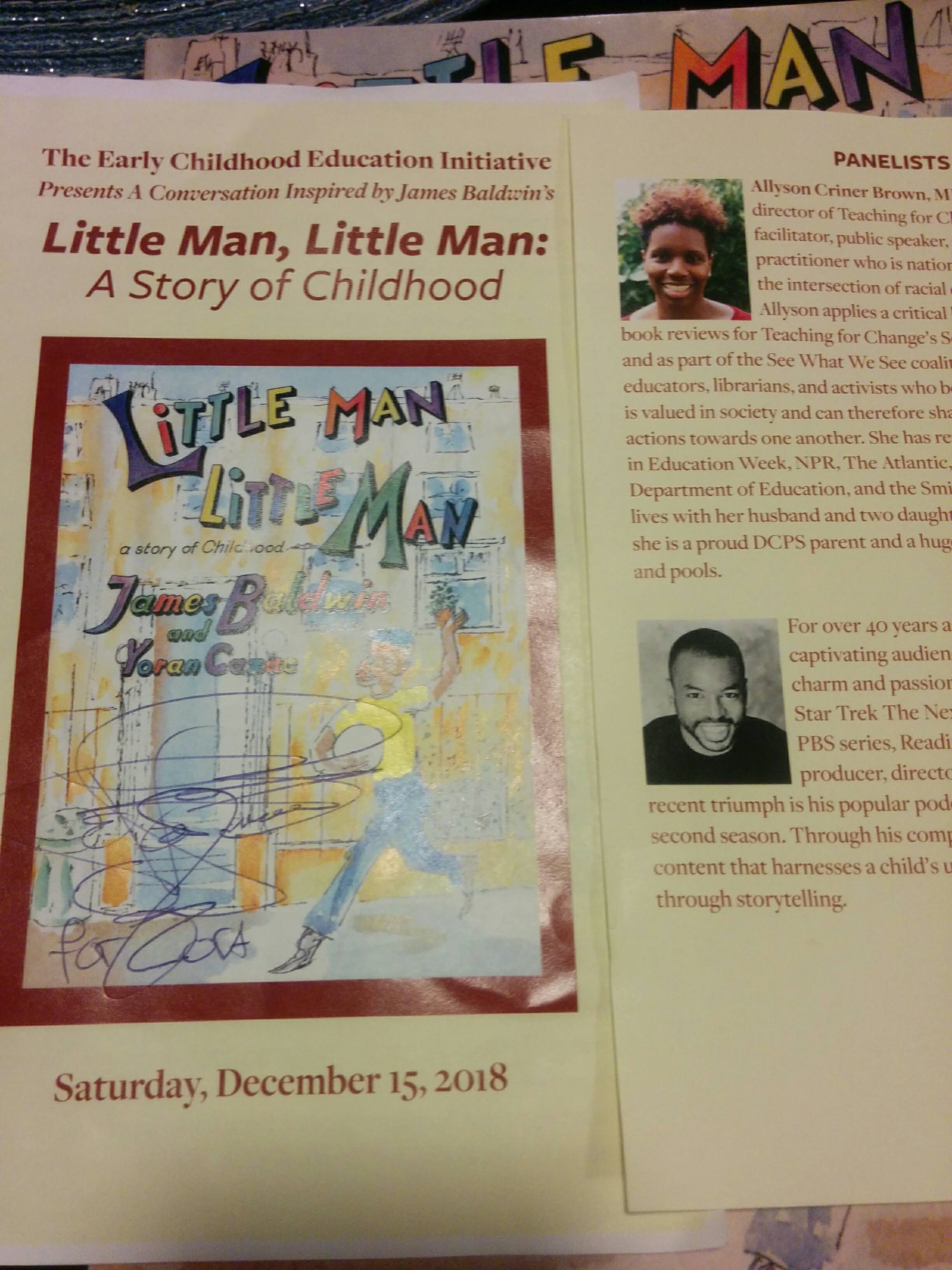

The museum’s Early Childhood Education Initiative collaborated with the events department to celebrate the re-release of James Baldwin’s only children’s book Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood. Baldwin based the work on his nephew and niece as they grew up in Harlem.

The festivities included a panel featuring noted actor and childhood literacy advocate LeVar Burton with Aisha Karefa-Smart, Baldwin’s aforementioned niece, who today is an author, educator, and public speaker. Judith Thurman of The New Yorker and Allyson Criner Brown of Teaching for Change completed the panel, which delved into in a riveting discussion of Baldwin’s work, the experiences of his niece and nephew, the cultural significance of Little Man, Little Man, and representation in children’s literature.

Criner Brown spoke as a book reviewer for Teaching for Change’s SocialJusticeBooks.org project and as part of the See What We See coalition of writers, scholars, educators, librarians, and activists who believe that books reflect what is valued in society and can, therefore, shape people’s attitudes and actions towards one another.

Among the many highlights, Karefa-Smart and Burton both read excerpts from the book, drawing audience members in with the imagery and Baldwin’s impeccable deployment of African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

When speaking about the importance of representation in children’s literature, Criner Brown framed the conversation using the concept of books as windows, mirrors, and sliding doors, as introduced by Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop in 1990:

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created and recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.[i]

Criner Brown and Thurman referenced the work of the Council on Interracial Books for Children (CIBC) beginning in the 1960s, noting that its legacy of analyzing children’s books using a critical literacy lens continues today in the work of the See What We See Coalition and SocialJusticeBooks.org.

Panelists also discussed the influence that books — and the lack of multicultural children’s books — had on their lives and lessons we can draw on to nurture young readers.

View a recording of the panel.

Teaching for Change would especially like to thank the staff at NMAAHC for the invitation and the panelists and speakers for their important contributions to this event, James Baldwin’s work, and children’s literature.

[i] Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, The Ohio State University, “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors” originally published in Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom. Vol. 6, No. 3 Summer 1990

Leave a Reply