Reviewed by Amy Rothschild

Book Author: Gary D. Schmidt

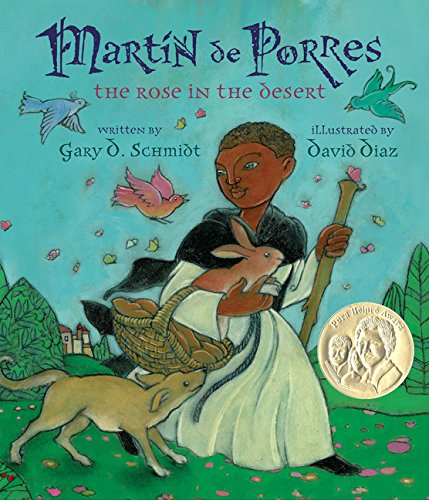

As an early childhood educator looking for excellent texts that promote diversity, inclusion, and equity, I looked forward to reading Martín de Porres: The Rose in the Desert, written by Gary D. Schmidt and illustrated by David Diaz.

The book tells the story of Martín de Porres, a brother in the Dominican Order in the seventeenth century who was canonized in 1962. Last fall, The Rose in the Desert won major honors in the world of children’s literature: a Pura Belpré Illustrator Award, a designation as an ALA Notable Children’s Book for Younger Readers, and an honorable mention for the Américas Award.

It is vital that children get the chance to hear stories about Afro-Latino history alongside other titles relevant to Black History. These titles must be age-appropriate and they must present their subject matter with dignity. Unfortunately, Schmidt’s Martín de Porres is neither age-appropriate, nor does it do justice to the subject.

The author’s choice of de Porres is a thorny one for an early elementary grade audience. The saint’s life requires the book’s creators to broach a variety of sensitive issues in an age-appropriate way: colonization, enslavement, rape, miscegenation and more. Rather than illustrate a moment from de Porres’s childhood or life, the author aims to tell his whole life story, pulling from each of those complex themes. De Porres was the son of an enslaved African in Lima and a Spanish royal. He became a surgeon’s apprentice and earned his role as a Dominican brother despite official bans on ordination of people of color. It is important that teachers are able to communicate sensitive topics to young children; however, the author takes on too much for most K – 2nd grade audiences and mistreats each issue.

The narrator dehumanizes people in poverty by providing a one-dimensional narrative of de Porres’s childhood: “hunger lived in their home. Illness was their companion.” The only other feature the narrator mentions is the stench. Such dramatic depictions deny the human relationships, adaptability, and strength of character that people in poverty, like all humans, possess.

Through confusing shifts in narration, the text reinforces the idea that being born poor or enslaved is a reason for shame. The author uses an omniscient narrator who constantly switches perspectives: from priest to noble to de Porres and back. For example, the narrator states that after thirteen years, every soul in Lima knew who de Porres was: “not a mongrel. Not the son of a slave. ‘He is a rose in the desert.’” Through this omniscient narration, the author fails to distinguish between the opinions of the masses and his own opinion. This conflation suggests to children that a marginalized identity is the same as a disgraced one, and that doing good works and achieving renown in fact means somehow erasing one’s origins.

Illustrations, while beautiful, are also problematic: the illustrator shows de Porres’ father, a rich man visiting from Ecuador, embracing his two children with a proud and distant stare as the children clutch him desperately. Such images reinforce the idea of the rich and noble savior as the path to righteousness and salvation for the poor.

As his concluding message, the author suggests that de Porres managed to usher in a post-racial society in Lima in the seventeenth century. The idea that racism against Afro-Peruvians and Afro-Latinos is a thing of the distant past just isn’t true. The author wishes children to believe that as a result of de Porres’ death, “across Lima’s plaza, the sweeping slave boys, and the Spanish Royals and the Indians . . . listened, and they began to sing.” The illustrator shows faceless figures holding hands. Meanwhile, scholars of Afro-Latino history insist that in “most countries with black or aboriginal populations, only a portion of its members has been accepted and has had more opportunities for social advancement.” The author could have connected this history to the present, as both Paula Young Shelton and Doreen Rappaport emphasize in their picture books on the Civil Rights Movement.

Contemporary American children’s literature is saturated with simplistic narratives of lone individuals who end racism and usher in a post-racial society. Unfortunately, another such narrative has been recognized with multiple awards.

Educators seek books that provide children with an appropriate window into issues of identity and power. Unfortunately Martin de Porres: The Rose in the Desert falls short of this goal.

Further Reading:

- Afro-Latinos and Black History Month

- Why it is Necessary that all Afro-Descendants of Latin America, the Caribbean and North American Know Each Other More

- An Updated Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books

Martin de Porres: The Rose in the Desert by Gary D. Schmidt

Illustrator: David Diaz

Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on June 26th 2012

Genres: Afro-Latino

Pages: 32

Reading Level: Grades 1-2

ISBN: 9780547822280

Review Source: Independent

SYNOPSIS: 2013 Pura Belpre Award for Illustration

As the illegitimate son of a Spanish nobleman and a former slave, Martin de Porres was born into extreme poverty. Even so, his mother begged the church fathers to allow him into the priesthood. Instead, Martin was accepted as a servant boy. But soon, the young man was performing miracles. Rumors began to fly around the city of a strange mulatto boy with healing hands, who gave first to the people of the barrios. Martin continued to serve in the church, until he was finally received by the Dominican Order, no longer called the worthless son of a slave, but rather a saint and the rose in the desert.

Leave a Reply