By Deborah Overstreet

In 2001, I wrote an article titled, Organize! A Look at Labor History in Young Adult Fiction, which was published in the National Council of Teachers of English’s young adult literature journal, The ALAN Review. In that analysis I examined how unions and labor were represented in historical fiction for young readers, and unfortunately, though not surprisingly, found that not only were they misrepresented, but that they were consistently represented negatively.

In the 20 years since the publication of that article, there have been changes in the state of organized American labor but have there been changes in books for young readers?

In the past few years, there has been a marked increase in worker unionization in companies that might once have seemed un-unionizable: Starbucks, Apple, and Amazon. Undeterred by massive and expensive union-busting activities from all three companies, workers are successfully organizing (Cahn, 2022; Farris, 2022; Mickle & Scheiber, 2022; Scheiber, 2022, (NLRB, 2023). While there are no declarations of martial law or Pinkerton thugs to attack and kill our current strikers and organizers, it’s difficult not to be heartened by resistance to common corporate anti-union tactics, including “captive audience” meetings where management forces workers to hear dubious anti-union talking points and retaliation against workers who organize. These workers can stand as present-day examples to students of workers insisting on coming together to create better working conditions.

As a classroom teacher in south Georgia, I was not a member of a union because there wasn’t a union to join. However, since becoming a professor, I’ve been fortunate to have union representation. Since then, I’ve always belonged to a union and am currently the secretary/treasurer and a delegate to the assembly of my university’s chapter of our statewide union. Unions enjoy popular support in my current home in Maine, which, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, ranks 14th nationwide for union membership. I encourage my undergrad students, who are all pre-service teachers, to join their unions upon graduation. This, I’m afraid, is not the message that they or their students will receive from literary representations of union and union workers.

In order to update my original analysis, I wanted to keep as many of the original criteria for book selection as possible. I was looking for young adult historical fiction that specifically and directly addressed unions and that were set from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s. My original work looked at books that featured women who worked in the textile mills of New England, women who worked in the shirtwaist factories of New York, and miners both in the east coast and western mountains. Since my purpose was to update my original research, I searched for books that were published in the last 20 years (2002–present).

Disappointingly, I only found eight novels that fit the bill: one mill story, Bread and Roses, Too (2006); five shirtwaist stories, Rosie in New York City (2003), Hear My Sorrow: The Diary of Angela Denoto, a Shirtwaist Worker (2004), Uprising (2007), The Locket: Surviving the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (2008), and Changes for Rebecca (2009); and two mine stories, Up Molasses Mountain (2002) and Fire in the Hole (2004). While there are good books that address the struggles of American workers, child labor reform, and labor safety reform, as before, I wanted to focus specifically on unions. Of the thousands of young adult novels published since 2002, only eight were directly about unions.

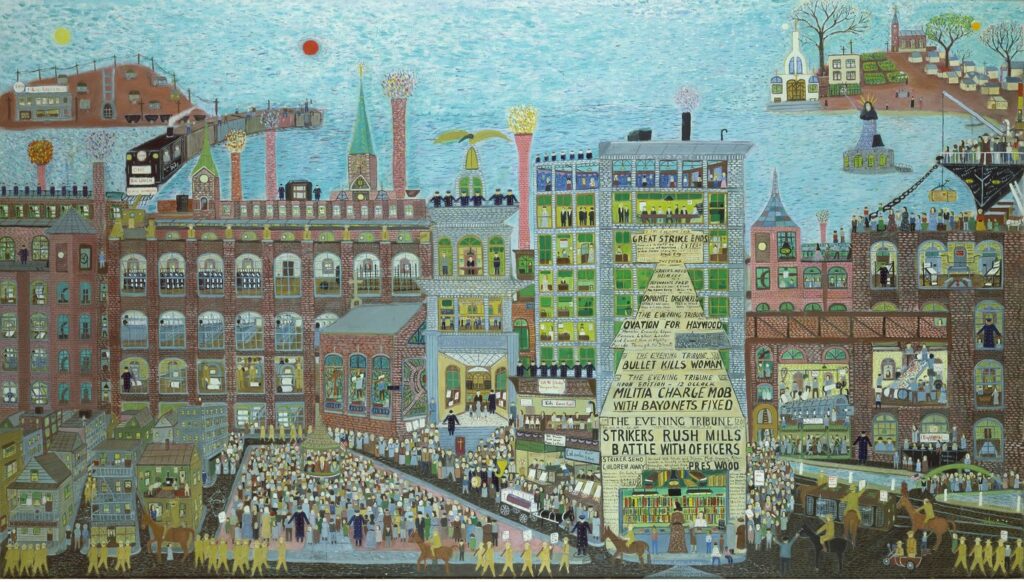

Not only is this a breathtaking dearth of books, but to my knowledge, there are no young adult novels that focus specifically on many of the major strikes in labor history. For example, in chronological order, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Homestead Steel Strike in 1892, the Pullman Strike in 1894, the Steel Strike in 1919, the West Virginia Mine Wars 1912–13, Matewan in 1920, the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921, and the Flint Sit-Down Strike in 1936 are all missing. In fact, I’ve found no young adult novel that focuses on the United Auto Workers in any way.

Changes for Rebecca, a garment factory worker book set in 1914 in New York, published in 2009, is the most recent text I could find that fit my fairly broad criteria. It’s especially upsetting to see that there hasn’t been a historical young adult novel focused specifically on unions published in the last 13 years. Perhaps the new energy brought by unionizing workers at Apple, Amazon, Starbucks, and countless smaller shops will change this and help readers (and publishers) develop an interest in our historical forebears.

Here is the 2001 article, followed by a 2022 update.

Organize! A Look at Labor History in YA Fiction (2001)

As a teacher and amateur historian, I have always been intrigued and inspired by early labor history. Mother Jones, Eugene Debs, and Big Bill Haywood were some of my historical heroes. Maybe that’s because I have labor union roots. One grandfather was a newspaper printer and belonged to the Newspaper Guild. My other grandfather and many uncles were coal miners — members of the United Mine Workers. Other uncles worked for General Motors and belonged to the United Auto Workers. My parents didn’t work in mines or factories, and we didn’t spend much time “talking union” at home. But yet, I grew up with a sense of the importance of unions and the courage of those who started and belonged to them.

It wasn’t until I decided to explore how labor history has been written in books for young readers that I realized that my deep respect and admiration for those workers who braved violence and blacklisting to create and maintain unions was hardly shared by friends or colleagues. They scoffed and hoped that I planned to explore rampant union corruption. Even knowing that I was most interested in the beginnings of the labor movement, predominantly between the Civil War and WWI, they were convinced that labor was always corrupt, unions were always unnecessary, and union membership was always indicative of greed and laziness. It’s crucially important that young people understand, as my friends did not, that everyone today benefits from sacrifices that union organizers and members made and how things we take for granted are a direct result of organized labor, e.g., child labor laws, 8-hour days, 40-hour weeks, minimum wage, and safety regulations.

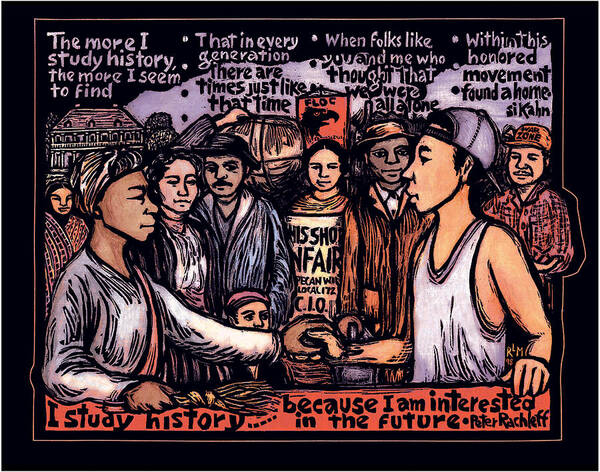

Our historical beliefs inform our interpretations of our present day world (Benson, Brier, Rosenzweig 1986). We’re likely to form those particular beliefs through a combination of textbooks, teachers, novels, movies, and nonfiction. In a major study of labor history in American high school history textbooks, Anyon (1979) found an alarming representation of the struggle of early labor — not only in the constant favoring of capital over labor, but even in which labor organizations were mentioned.

. . . textbook characterizations of labor history are strikingly narrow and unsympathetic to the more radical segment of the union movement. . . . Most strikes are not even mentioned, and although there were more than 30,000 [between the mid-1800s and early 1900s], the texts describe only a few. Fourteen of the seventeen books chose among the same three strikes, ones that were especially violent and were failures from labor’s point of view. (p. 373)

When students are taught using textbooks with such information, their beliefs are swayed. History textbooks, like all histories, legitimize only certain aspects of the whole possible story ― usually those parts of the story that benefit and enhance the most powerful groups in society. Very narrow information is presented as an objective and complete account ― never as the sliver that it actually is (Williams, 1977). This selective tradition is perpetuated in textbook conceptions of labor history.

The history of labor is a story of the people, but ironically Anyon found that stories of actual laborers are virtually ignored in the texts. Even within organized labor, Anyon found that the AFL (American Federation of Labor) ― a more conservative and exclusionary group of trade unions ― was most frequently emphasized. The far more radical and potentially powerful IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) is marginalized through its constant absence. The textbooks grudgingly abide only traditional trade “unions that have accepted the legitimacy of, and been empowered by, the U.S. business establishment” (Anyon p. 379).

Most startling is that Anyon’s landmark 1979 study is the most recent examination of labor in school history texts. A diligent search of education databases yields nothing more current. This in itself demonstrates an amazing neglect of this crucially important part of our nation’s past. But ultimately, this study isn’t about textbooks ― they just serve to provide background.

It’s no wonder that people who have had little or no experience with unions can have such virulently negative attitudes toward them. Reproduction theorists believe that schools and school curricula are structured in such a way as to reproduce and legitimize the dominant culture and existing power relationships (Weiler, 1988). Those who control the means of production are certainly served by having potential workers convinced of the evils and futility of organized labor. School history textbooks fall squarely within this tradition.

Fortunately, students are not exclusively products of their historical education. Production theorists are concerned with the ways that both individuals and groups refuse to accept the influences of the ideological forces of a culture ― textbooks, for example. Teachers and students can resist, assert alternate interpretations of history, and create their own meanings (Weiler, 1988). Historical fiction can become part of that resistance ― especially when it contradicts textbooks, provides a different perspective, or gives voice to those not represented in conventional history. In some very real ways, these twelve labor history novels do serve in this capacity.

To this day, America has the least developed and most opposed labor movement of any industrialized nation. While this sad fact is not entirely the result of the vilification of organized labor in textbooks and popular culture, it is surely a factor. Anyon found that the textbooks “promote the idea that there is no working class in the United States and contribute to the myth that workers are middle class” (p. 383). The virtual absence of the laboring class or union workers on television and in movies contributes to their marginalization. When U.S. workers cling to the popular culture-fed delusion that they are middle class, perhaps their desire for union affiliation is muted.

The Novels

Given how sparsely labor is mentioned in textbooks, I was surprised to quickly find many novels and even more nonfiction books about various aspects of labor history. Because of limited space, I chose twelve novels dealing with mill workers, shirtwaist workers, and miners. Mill and shirtwaist novels exclusively involve female workers; mine novels feature male workers. I was especially interested in novels set from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s because this is a period in which some of the most important changes in American labor occurred (Meltzer, 1991).

Three overarching questions drove this research. The first is pre-union: What were working conditions? The second involves attitudes: What do laborers, bosses, owners, police, and others say or think about unions? Finally: What were the unions’ goals? What were the unions like? What did they accomplish?

Mill Novels

The two earliest books are set in the mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1836 and 1845. Even though the young women protagonists are already laborers, they’re barely adolescents. In A Spirit to Ride the Whirlwind (1981), based on true events in 1836, we meet Binnie Howe, whose mother runs a company boarding house. The mills control every aspect of the women workers’ lives. They’re only allowed to live in company-approved quarters and are required to attend church. There is rampant bigotry against the Irish workers who are largely denied jobs in the mills.

In Spirit, mill bosses set the clocks back so that women are required to work extra time each day. A “premium” system is instituted wherein bosses, but not workers, are rewarded for increasing the women’s pace. When the mills are closed for repair or bad weather, the women are not paid. Conditions worsen as workers are required to tend more machines and to work more quickly for no increase in pay. Women can be fired on a whim for any complaint or for questioning a boss. If workers are fired or leave the mill, they are blacklisted in all other mills.

When talk of a union begins, some women are wary but intrigued, but many are horrified, describing unions as “improper, if not immoral, for women to engage in” (p. 168). The newspapers call unions dishonest. Despite this, enough women organize and hold a “turn-out.” As women from each mill leave, they hold a rally where a woman speaks to the crowd:

In Union there is power. And we must have, we will have the power to press for and win a decent wage. If we organize ourselves to stand fast. . . if we hold out. . . together, we will prevail. To participate in public protest is not enough. We must organize. (p. 175)

Eventually, the mills must close for lack of workers. Some minor union demands are met. Some workers are allowed to return to their jobs, although union organizers are fired.

Lyddie (1991) is probably the best known book in this study. The working conditions in the mill and the unfair management practices are described in frightening detail. Also present is the vitriolic racism of the workers toward the Irish, who are assumed to be willing to work for even lower wages than the women. Lyddie thinks that Irish immigrants are waiting to prey upon her position. She “could not fall behind . . . else her pay would drop and . . . one of these . . . papists would have her job” (p. 100).

Lyddie (1991) is probably the best known book in this study. The working conditions in the mill and the unfair management practices are described in frightening detail. Also present is the vitriolic racism of the workers toward the Irish, who are assumed to be willing to work for even lower wages than the women. Lyddie thinks that Irish immigrants are waiting to prey upon her position. She “could not fall behind . . . else her pay would drop and . . . one of these . . . papists would have her job” (p. 100).

Lyddie becomes friends with Diana, another laborer who is known as a radical for her union beliefs. In the evening, the women talk in their boarding houses about the intolerable conditions. They compare themselves to “black slaves” and consider signing a petition to decrease the work day to 10 hours. As in Spirit, the women have differing opinions on the petition and unions:

“It does no good to rebel against authority.”

“Well, it does me good. I’m sick of being a sniveling wage slave.”

“I mean it’s…it’s unladylike and…and against the Scriptures.”

“Against the Bible to fight injustice?” (p. 92)

Lyddie takes no part in the discussion. She wants only to earn money and isn’t interested in working to better her situation. As conditions worsen, Lyddie stays out of all discussion of organizing. The work turns her into a mindless drone and eventually she leaves the mill. Through Diana, the Female Labor Reform Association that operated in Lowell is mentioned, but Lyddie is mostly focused on the misery of the workers. The 10-hour movement isn’t successful in the novel, and even though Lyddie is treated atrociously, the idea of a union still holds no appeal for her. The author, Katherine Paterson, refuses to take a stand on unions. They are positively represented, but she allows Lyddie, through her own apathy, to dismiss them as worthless.

Shirtwaist Novels

The three novels about shirtwaist sweatshop workers are all set on the Lower East Side of Manhattan between 1908 and 1911. Each features a Russian Jewish immigrant family struggling to assimilate and to survive in grinding poverty. The protagonist is the younger family member of the shirtwaist worker and has often briefly worked in the sweatshop herself. The first two novels involve many of the same historical events. Call Me Ruth (1982) and East Side Story (1993) both tell of the famous shirtwaist factory workers’ strike of 1909. The characters’ immigrant status is a major component in these stories. When unions become an option, many immigrant workers are reluctant to join because of the perception that unions are anti-American.

Wretched working conditions and unfair labor practices are described in heartrending detail. Workers are paid by the piece, work 12 (or more) hour days, provide their own supplies, get no breaks, work in intolerable temperatures in locked rooms, and are classified as “learners” for years so as to be paid at a lower rate. Sexual harassment by bosses is as feared and common in the shirtwaist factories as TB and fires. In Call Me Ruth, we meet Fannie, a young widow working to support her family. She is caught up in the labor movement as more and more women join the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and win minor victories. A pivotal scene is based on an actual historical event. At the Cooper Union Hall, an enormous group of women gather to hear union speakers. The Triangle Shirtwaist factory was already on strike and the leaders wanted to call for a general shirtwaist strike. Clara Lemlich, a very young woman and an actual historical figure, leapt to the stage interrupting the droning male speakers who were urging caution, and demanded that the women take action. The crowd was so moved that a general strike was called.

Fannie’s daughter is shamed when her teacher rails against the strikers in class:

. . . the pickets were a disgrace to this country and to God. [Miss Baxter] read us an article in the paper which told how [a judge sentencing a striker said], “You are on strike against God and Nature whose law it is that man shall earn his bread by the sweat of his brow. You are on strike against God.”

She said it was a disgrace how thousands of young women betrayed their own sex by acting in such an immoral fashion. It was bad enough. . . when men took to the streets and promoted violence, but for women to behave like wild animals was a sign of the wickedness of the times. She warned us that unless people exercised self-control and showed obedience to authority, this country and all it stood for would be destroyed. (p. 107)

Miss Baxter’s attitude was a common one. As the women picket, they are harassed and assaulted by the police and hired thugs. They are regularly arrested and imprisoned. The strikers receive some minimal financial support from a group of rich women who formed the Women’s Trade Union League. After many arrests, Fanny becomes a union leader and the strike is resolved with the women gaining a few benefits. Unfortunately, Call Me Ruth doesn’t mention that the all-male leadership of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union were completely opposed to the strike, wouldn’t help organize, and wouldn’t supply strike relief or legal aid (Dash 1996).

Less accurately, East Side Story (1993) recalls some of the same events. Leah works at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and is a union organizer. When she and sister, Rachel, arrive at Triangle one morning, the workers are picketing. Management tells the women that there is now less work and they are all promptly fired, but Rachel suspects the firing is a result of Leah’s union work. This makes no sense. It was then a common and legal practice to fire workers for having any union affiliation. Firings were very public in order to frighten others away from unions, so Triangle would never have kept this motivation secret.

Without much detail, the strike ends, although Triangle workers’ demands aren’t largely met. But the women still believe that they have accomplished something.

“How can you go back to work if you have lost?” Rachel asked Leah. “The owners are still going to lock the doors, and the fire escapes still don’t work. And they haven’t agreed to give us fair pay or shorter working hours.”

“It’s true, Rachel. We lost,” Leah said. “But we worked hard, and a lot of other people won. Besides, this was the first time that women really spoke out and were heard.”

“I still don’t understand,” Rachel said. “Was it worth the trouble?”

. . . “Yes, Rachel. We convinced workers in other factories to go on strike, too. And a lot of them got what they asked for. We haven’t given up hope here yet. One day we’ll get what we want.” (p. 60)

Of course, the shirtwaist factory strike in 1909-1910 was very significant in labor history, but it was not “the first time that women really spoke out and were heard.” Female-only unions had been striking since the early 1800s. The Lowell workers struck as early as 1834 (Meltzer 1991).

Fire! The Beginnings of the Labor Movement (1992) about the famous Triangle Factory fire suffers from an overstated title — the labor movement began long before the fire in 1911. Rosie works in the factory. A union is mentioned, along with the safety demands that it should make — fire escapes, unlocked doors, a sprinkler system (never mind that these weren’t in use at the time).

Papa thinks that Freyda and Rosie should just be grateful that they even have jobs and that no matter how bad working conditions are here, they’re better than life in Russia. The Saturday morning fire is described only vaguely. There is a mention of burned bodies on the sidewalk, but nothing of the many women who jumped to their death rather than burn (Dash 1996). After 146 women die, the Jewish male characters blame the deaths on the fact that the women were working on the Sabbath, rather than on the unsafe working conditions.

“If only [she] had listened to me,” said Uncle George. “If only she hadn’t gone to work on the Sabbath” . . . .

“That’s not it,” [Rosie] blurted out. “Didn’t you hear Freyda? Ida? . . . The doors were locked. The windows stuck. Scraps all over the floor. Oil-soaked scraps. Hundreds of sewing machines packed into one room. Fires in the stairway. Only one fire escape, and it didn’t even reach the ground.” (p. 45)

The story ends in a bizarre ILGWU meeting to commemorate the dead. The male union speaker tells the women that their “future lies in unions. If you organize yourselves, you gain strength and get better working conditions” (p. 49). However, the major shirtwaist strike had already happened — unsupported and even denounced by the ILGWU. Many of the women were union members at this point and had been for years (Dash 1996).

There is little mention in these three novels that the majority of shirtwaist workers were recent Italian or Russian Jewish immigrants. These two groups, who seldom spoke English, were often pitted against each other by the bosses who played on the immigrants’ fear and racism. Workers of different ethnic backgrounds were frequently seated beside each other so that they could not communicate ― having no common language. This also prevented them from organizing or from seeing themselves as allies (Dash 1996).

Mine Novels

The history of miners’ attempts to organize and resist exploitation is long and bloody. Some of the worst violence against laborers was committed by companies resisting the unionization of miners (Kornbluh 1988). Mine workers in all seven novels register the same grievances: the working conditions were gravely dangerous, the pay was minimal and in company scrip, the mine bosses regularly cheated miners paid by the ton by underweighing coal. Reminiscent of the mill workers in Lowell, mine owners controlled every aspect of the miners’ lives. Because of mine locations, miners were forced to live in “company towns” where the mine owners also owned all houses, stores, churches, newspapers, and schools. The miners had to purchase everything at the company store — often on account, which was settled with their pay. Rent, supplies, etc. were also deducted. Miners barely broke even.

The first five novels are set in the anthracite coal mines in Pennsylvania between 1897 and 1902. In The Candle and the Mirror (1982), set in 1897, Emily is a suffragist and labor organizer working in the coal fields organizing Italian and Slovak miners and their wives. Just as in the shirtwaist factories, mine bosses consistently pitted these groups with no common language against one another. As long as miners fought among themselves, they hadn’t time to fight their true oppressor. The union organizers, Emily, Paolo, and Jan, speak to the miners in their own languages, although we are never told which union they represent. The United Mine Workers (UMW) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) both organized miners in Pennsylvania.

The IWW was the most radical of all unions, and despite its enormous influence on the history of labor, is never mentioned by name in any of the novels. Emily writes to a local newspaper about the miners’ desperation:

The owners don’t believe we’ll strike. They don’t realize how little the miners have to lose. Do you know that when the owners recently found out — through their company banks — that the miners were managing to save money to bring their families over from Hungary and Italy, they slashed wages. They figured the miners were more controllable if they had no savings! (p. 123

Eventually Emily convinces the miners’ wives to occupy the company store and destroy “the Book” of accounts, where the miners are regularly overcharged and cheated.

There is a brief mention of breakers ― this was how boys as old as six or seven began their mine work. Their job was to separate coal from rock and slate and to sort the coal lumps as the mass of coal and rock tumbled down long chutes. The job was dangerous and back-breaking, and paid seventy-five cents for a 60-hour week.

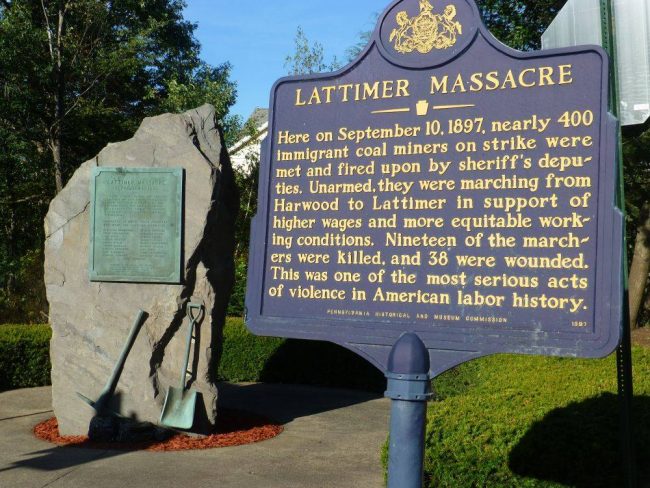

A Coal Miner’s Bride (2000), also set in 1897, culminates in the Lattimer Massacre where 19 unarmed striking miners were killed and at least 50 were wounded when their march was fired upon by the local sheriff and other “deputized” men. Focusing largely on Polish immigrant miners, we are again shown bosses who encourage segregation of different ethnic communities as a way to prevent labor solidarity ― this time coupled with anti-immigrant bigotry. Immigrant characters are skeptical of joining an “American” union, although this isn’t historically accurate. The UMW, of all unions, always welcomed all races and ethnicities, understanding that unions wouldn’t otherwise be effective. When conditions finally become unbearable, the immigrant miners strike. Their demands included raises for men who work underground, a reduction of blasting powder prices (miners paid for their own supplies), and a restoration of recently lowered wages. Unfortunately, we aren’t given any information about how the strike was resolved. If nothing else, the Lattimer Massacre did greatly increase union membership in the mines.

Trouble at the Mines (1987) is based on a 1899 strike in Arnot, Pennsylvania. The story is told by Rosie, the daughter and niece of miners. After miners are killed in a cave-in, the men begin to organize to demand more safety measures. They worry about the backlash experienced by other miners who tried to unionize. “. . . Those miners demanded their pay not be cut, the first thing the company did was fire the ringleaders to scare the others. And when that didn’t work, they evicted people from their homes” (p. 6). These were common tactics early in any strike or effort to organize.

Rosie’s father and uncle are fired for trying to form a union, but the families hadn’t yet been evicted. The mine owners claim there isn’t money for improved safety or raises (miners were paid sixty-five cents per ton of coal they mined). When the owners threaten to close the mine if the miners won’t return to work, many want to return — even if it means that none of their demands have been met. This rips apart many families.

The famous labor organizer Mother Jones, often called “the most dangerous woman in America,” who actually worked with miners in Arnot (Josephson 1997), appears in Trouble. She encourages the miners to stick together and organizes the women to prevent scabs from going back to work. The women use pots, pans, and brooms to prevent any man from entering the mine. Mother Jones finds food for miners who have been on strike for months. Largely through her encouragement and the women preventing scabbing, the miners hold out for eight months and are eventually given a small raise and some safety improvements. She also encourages the miners and their families to forgive those who scabbed and to accept them into the union.

Dear friends, they were frightened. Frightened by hunger, frightened by sickness, they betrayed their brothers and sisters. . . . But we fought for them anyway, and we have won for them too. And now that we’re victorious . . . we must be as generous in victory as we have been faithful and brave in battle. We must forgive those who lost courage and fell by the wayside. (p. 79)

The Arnot strike was marginally successful and less violent than others to come.

Breaker (1988), set in 1902, is told by Pat McFarlane, a breaker boy. The story begins with a cave-in where all the trapped miners are killed, including Pat’s father. After reminiscing about mine stories his father told him, Pat realizes that the mine owners are only willing to make changes after a disaster and this angers him. Pat can’t understand why his father would never support a miners’ union, which he incorrectly refers to as a trade union instead of an industrial union. This distinction may sound slight, but its implications were enormous for organized labor. No novel in the sample ever discusses the differences. Trade or craft unions (usually only for skilled, white, male workers) organized across industries, e.g., all electricians, all welders, etc. AFL unions were trade unions. Industrial unions organized within an industry, e.g., all railroad workers, all miners, etc. The IWW was an industrial union and its main legacy is creating a momentum for industrial unionism (Flagler, 1990). Trade unions made strikes virtually impossible. If railroad workers wanted to strike, then all the trade unions involved must agree and be coordinated and willing to support “unskilled” workers. This seldom happened and also left “unskilled” workers unrepresented. The miners’ unions (UMW, WFM, etc.) were all industrial unions (Lens 1985).

Throughout Breaker, tensions between Irish, Welsh, Slovak, and American miners are encouraged by mine owners. Interestingly, a new teacher arrives at the local school. The previous teacher “had drilled into her pupils that they should be grateful to the company for providing jobs and housing, a doctor and a school” (p. 63). The new teacher sends a different message:

You miners work longer hours and at greater peril than most other men. If you are paid by the car, the cars get bigger, if you are paid by the ton, the tons get heavier. If you are hurt or die in an accident, there is seldom any compensation. If you complain about poor working conditions, you will likely lose your job. If you refuse to buy overpriced goods at the store, you may be threatened or fired. Join the union and you are suspect, strike and you may be cut down by the Coal and Iron police. Your families suffer as you do. A few operators and rich railroad magnates control thousands of lives. (p. 62)

The teacher explains that workers were in such dire straits because they refused to organize on a large scale. As long as one mine was open, a strike at another made little difference.

The men decide to strike and John Mitchell, the UMW president who was invariably anti-strike, grudgingly supports them. The owners bring in armed guards to “protect mine property.” The union leaders warned the workers not to “provoke the Coal & Iron police. Operators want the outside world to believe that strikers are dangerous, in order to get public opinion on their side” (p. 96). George Baer, the owner of the Reading Railroad, writes a letter to the newspaper to condemn the strike and the union:

The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for— not by labor agitators, but by Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given control of the property interests of the country . . . . (p. 136)

This social Darwinism elevated to divine right was a frequent attitude of industry’s owners.

Violence finally erupts. Sheriffs protecting scabs brought in by the owners are killed in a scuffle. Even though miners are innocent, they’re correctly convinced they’ll be blamed. In a common move, the governor sends in the National Guard to protect mine property and scabs. Never a neutral force, National Guard and federal troops were often used by mine owners to break strikes and to kill strikers. The strikers return to work and Clarence Darrow represents the miners in national hearings. Even so, they only win a 10% raise. None of their other demands are met.

Theodore Roosevelt: Letters from a Young Coal Miner (2000) is a bizarre and fictional exchange of letters between a 13-year-old miner and President Roosevelt regarding the same events as Breaker. Roosevelt appears sympathetic, but unwilling to help laborers. His sympathies are likely overstated given his well-documented apathy toward child labor and workers in general (Colman, 1994). This novel, like Breaker, concludes with the hearings after the anthracite coal strike in 1902. One of the miners’ grievances had been that the weighing agents regularly underweighed the coal of miners who were paid by the ton. Roosevelt’s commission decreed that if miners wanted coal weighed fairly that they must pay for the weighing agents themselves. This was a defeat for miners, yet Armstrong has her characters pleased with the decision. In actual history, Mother Jones, who worked as a UMW organizer, felt that Mitchell had “caved in to the demands of the mine owners because he was flattered by the attention he got from [Roosevelt]” (p. 43).

The final mine novels take place in Colorado. Set in 1911, On Fire (1985) tells the story of Yankee, whose union brother was killed in a strike, and Sammy, whose brother is a scab. The story starts shortly after a strike has already begun. This novel paints everyone involved in the strike ― miners, union members, scabs, owners, families, and townspeople ― as violent thugs unmotivated by principle and only interested in how much destruction they can cause.

Even though miners have a multitude of legitimate grievances, Yankee wishes she could force the owners and the miners to “come to an agreement and stop this craziness” (p. 91). Throughout the book, senseless violence is committed on both sides. Even though we’re never told the strikers’ demands, we’re told they’re not met. The book ends as the strike ends and one character cynically says, “Mr. Ekert can tell his boys he won them a little something and they ought to get back to work. And Mr. Stoker can tell his bosses they didn’t lose a thing, and ought to get back to their partying. I guess that’s called ending” (p. 202). On Fire, a truly mediocre book, takes no real stand on unions or labor issues. The author seems to sympathize with the inhuman conditions, but then presents union members and leaders as thugs.

Frankie (1997) tells the story of the famous Ludlow Massacre in 1914. The novel begins as the miners’ families have been evicted from their company houses because of an impending strike. Luke’s father delivers milk to the miners’ camp as they await the arrival of tents and blankets from the UMW. The situation escalates when some Greek miners return to their homes to retrieve personal possessions and are killed by the local sheriff after being arrested for trespassing.

Scabs are brought in from out of state. Mother Jones arrives to support the strikers and delivers her famous line “you’ve got to pray for the dead, but fight like hell for the living!” (p. 45). She tells the union men to encourage the scabs to join the union. After several months of the strike, Baldwin-Felts guards are brought in to intimidate the strikers. There is constant minor violence until the guards finally kill several miners and the miners retaliate.

The governor of Colorado calls in the state militia to keep the peace, although in actuality, the militias were never an impartial presence and were used as mine guards to protect the interests of the owners and punish the strikers (Kornbluh 1988). Mother Jones is arrested. Escalating over the months that the miners and their families freeze in their tent communities, tensions come to a head. The Baldwin-Felts guards and the militia open fire on the tent communities and the few armed miners fire back. After spending an entire day shooting into every tent and at unarmed miners and families, the guards douse the whole area with kerosene and lit it afire. Many trapped families burned to death. Eventually 33 miners and their families were killed and hundreds were wounded. Even after this, the strike was not settled in favor of the miners.

While not as nihilistic as On Fire, the main point of Frankie seems to be that these are not black and white issues (although they certainly seem very straightforward both in history and in this novel) ― they’re too complicated to understand fully and that there is good and bad in both labor and management. This may be more accurate today, but was a gross oversimplification at that time.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that these books can be applauded for examining the experiences of ordinary people as opposed to famous ones, it is unfortunate that the focus remains so tightly on the characters instead of the broader historical and economic context in which the novels were ostensibly situated. What picture of collective action is presented? Generally, young readers are shown individuals ― not groups working in concert. Novels do traditionally focus on individuals, but authors could have chosen to focus on individuals and/in the collective. Even when the workers are part of the union, they are still depicted in the novels as separate from the group.

While all of the novels focused on the monstrous working conditions, the miserable grinding poverty of the workers, and the callous apathy of the bosses, they all also deftly avoided any meaningful discussion of the inherent injustices of capitalism, class structure, and the belief in social and economic Darwinism. None of these novels makes any meaningful attempt to situate their narrative within any larger historical, political, or economic picture. The novels seldom examine in any detail the accomplishments or purposes of organized labor and they all miss the opportunity to examine the long-term impact that unions may have had on the laborers’ lives.

The authors of these twelve 12 books seem largely to be pro-labor, although their specific beliefs aren’t always clear. Therefore, none of the books are as informative as they might have been. But even with these drawbacks and their widely varying quality and appeal, these labor movement novels still serve an important purpose and should be used in conjunction with labor nonfiction. They can help teachers to humanize this facet of our history and to provide a different perspective than is likely to be found in history textbooks. The only famous union organizer who appears is Mother Jones. Where is Eugene Debs? Bill Haywood?

Perhaps students might compare labor novels with both history texts and primary source documentation. This would be a perfect opportunity for critical reading and thinking. Students would be able to act as historians and scholars of literature as well. Even though these novels are far from perfect, and even the best novels should never be used uncritically in a social studies curriculum, they offer a starting place for considering the perspectives of those whose voices are seldom heard. Or as Green (1997) suggests, students can use these novels to begin to examine why U.S. companies “have insisted on such total control of the workplace and of the people in their employ and why private and state forces intervened so often against workers and their unions” (5). Allowing laborers’ voices to be heard can also serve to teach young readers that ordinary people working together can effect great change ― even if it is often a slow process.

Updates: 2022

Mill Novels

Bread and Roses, Too (2006) is doubly unique in that it’s the only young adult novel about the Lawrence mill strike of 1912, and it’s also the second book in the sample written by Katherine Paterson, who also wrote Lyddie (1991) about the 1840 mill strikes in Lowell. Bread and Roses, Too is based on a real strike that began in January 1912 when Polish workers walked out of the mill after their pay was shorted. They were followed by thousands of other mill workers (Zinn, p. 335). The novel picks up the story as the strike begins. This unfortunately doesn’t allow us to see the working conditions that the strikers are protesting.

In the earlier mill novels, Irish workers in Lowell are discriminated against, but by 1912 in Lawrence, Irish workers have advanced and more recent immigrants had the lowest and least paying jobs. While Lawrence was multinational and multilingual, Bread and Roses, Too focuses primarily on Italian workers. Sixth grade Rosa’s mother and sister work in the mills while she attends school. Rosa’s teacher, Miss French, rails against the strike, calling it “godless and lawless” (p. 60) and against the strikers and anyone who supports them because they’re “animals” (p. 96). At least at first, Rosa parrots her teacher’s vitriol, even though she fully understands the working conditions in the mills and the penury of the mill workers. She blames the strike on the union, assuming that the “union was making sure” that “the strike would go on” (p. 115).

In the earlier mill novels, Irish workers in Lowell are discriminated against, but by 1912 in Lawrence, Irish workers have advanced and more recent immigrants had the lowest and least paying jobs. While Lawrence was multinational and multilingual, Bread and Roses, Too focuses primarily on Italian workers. Sixth grade Rosa’s mother and sister work in the mills while she attends school. Rosa’s teacher, Miss French, rails against the strike, calling it “godless and lawless” (p. 60) and against the strikers and anyone who supports them because they’re “animals” (p. 96). At least at first, Rosa parrots her teacher’s vitriol, even though she fully understands the working conditions in the mills and the penury of the mill workers. She blames the strike on the union, assuming that the “union was making sure” that “the strike would go on” (p. 115).

The IWW, an industrial union, was highly involved in the strike and makes an appearance in the novel — the only time in any novel in this sample. In an odd, textbook-like paragraph, mid-novel, the IWW is introduced as:

. . . simply the “Wobblies.” The Wobblies’ motto was “Solidarity.” That meant they weren’t like the big unions, who represented only one kind of worker. The Wobblies believed in standing united across various skills and national origins. (pp. 127–8)

Joe Ettor, an Italian IWW organizer, is the first to come to town, shortly after the governor has called out the militia, something we’ve only seen in novels about miners. From the beginning, Ettor advises both nonviolence and the ideals of an industrial union:

My fellow workers, by all means make this strike as peaceful as possible. In the last analysis, all the blood spilled will be your blood. And above all, remember they can defeat us only if they can separate us into nationalities or skills. (pp. 53–4)

This is a very different approach to organizing than traditional trade unions, which organized by skill and rarely included immigrants or women. After the militia kills a Syrian striker and Ettor is arrested for inciting the conditions that led to the murder, the far more famous Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn come to lead the strike ― organizing and fundraising. They instantly enlist help from workers everywhere to support union soup kitchens and strike funds.

After a month of striking, The Call, a socialist newspaper in New York proposed that strikers send their children to supportive families in New York, Philadelphia, and Barre, Vermont. The idea was that if strikers knew that their children were well-fed and taken care of, they could hold out much longer. This had been a fairly common practice in European strikes, but not in the United States (Zinn, p. 336). Along with other children, Rosa is sent to Barre to a warm and generous welcome. After a few days, one mother demands that her children be returned because mill owners and agents falsely convinced parents that their kids were “being harshly treated in Vermont, that they were no more than slaves to the rough and drunken stonecutters” there (p. 216).

When the militia attacks a group of mothers sending their children to Philadelphia, there is a national uproar, and the strike is over. The owners agree to all the strikers’ demands. Like most of the novels in this sample, there are few dates given until the “historical note” at the end, which makes it far more difficult for readers to understand how long, for example, a strike may last or a striker may languish in jail.

Shirtwaist Novels

Novels about shirtwaist workers continue to be popular, likely because of their connection to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in March 1911. Three of the five newer shirtwaist books are directly, though not exclusively, linked to the fire. Unlike the earlier shirtwaist novels, the “Dear America” book Hear My Sorrow: The Diary of Angela Denoto, a Shirtwaist Worker (2004) and Uprising (2007) both feature Italian shirtwaist workers. The shirtwaist workers were a mix of Italian and Russian Jewish immigrants along with Americans. Also unlike the earlier novels, there’s no assumption in any of these five books that joining a union is anti-American.

Rosie in New York City: Gotcha! (2003), Hear My Sorrow (2004), and Uprising (2007) all begin before the “Uprising of 20,000,” the general shirtwaist strike from November 1909 to March 1910. Like the earlier shirtwaist novels, these books chronicle the conditions before the strike, the famous Cooper Union meeting including Clara Lemlich’s inciting speech, the general strike, the lack of support from the male leadership of the ILGWU, the tenuous support of the Women’s Trade Union League, the brutalization of the strikers by thugs and police, and the disappointing and infuriating lack of positive results. Rosie (2003) ends after the strike; Hear My Sorrow (2004) and Uprising (2007) both end shortly after the Triangle fire.

Rosie’s (Rosie in New York City, 2003) mother is a shirtwaist worker and a union organizer. When Mama falls ill from exhaustion and injury from a beating during a prior strike, it’s up to 11-year-old Rosie to temporarily take her place and support the family. During her first day on the job, Rosie is exposed to the harsh working conditions we see in all the shirtwaist novels: workers having to provide their own supplies, being fined for talking, not being paid for extra work, being locked in the crowded factory, and bosses speeding up clocks during worker lunch break. Even though it’s mentioned in The Locket (2008), in Rosie, we actually see underage workers hide when inspectors turn up at the factory. Rosie is locked in a tiny, filthy bathroom, and her friend Marie is shoved into a crate.

Since Mama had been one of the organizers of the now-famous Cooper Union meeting where shirtwaist workers were to decide how to proceed, Rosie decides that she must attend and is energized by Clara Lemlich’s call for a general strike against the urging of the all-male union leadership. The strike is approved, and the next day, Rosie and the other women walk out. They immediately understand that as picketers, they’ll be in danger from “the brutes the bosses hire to beat us and intimidate us” (p. 79), which is exactly what happens. Many are beaten and arrested, including Rosie.

Rosie is horrified to see that there are plenty of scabs who are willing to continue to work during the strike. She and the other picketers understand that if workers are willing to scab, then “why would the bosses ever recognize the union? Why would they give [workers] anything?” (p. 80). The novel includes several pages of a discussion about scabbing. A union organizer advises the picketers to “try to convince the scabs that they are hurting themselves as well as us” (p. 92). Like Mother Jones in Trouble in the Mines (1987), Rosie’s mother urges her to forgive scabbing workers, saying that “they’re afraid of letting their families down, of not eating, of being hurt while picketing, of the cold” (p. 97). When Rosie rightly points out that the strikers are afraid of the same things, Mama has no useful answer. When Rosie’s friend Maria is pressured by her father to scab, Rosie is indignant and correctly insists that “if everyone doesn’t strike together, we’ll never get the owners to agree to our demands” (p. 104).

When the owner of their small shop offers shorter hours and vaguely better conditions, but no union recognition, a male union organizer says that it’s a good deal and advises that the women accept it. However, the workers know that without union recognition, no offer is acceptable because no new conditions would be guaranteed. They vote no, and eventually the owner gives in and recognizes the union.

Fourteen-year-old Angela is the protagonist of Hear My Sorrow (2004). Both she and older sister Luisa are shirtwaist workers and are the older daughters of a large Italian immigrant family. They work at a smaller shirtwaist factory, where conditions are miserable. Because she speaks English, Angela befriends Sarah and Clara, two slightly older Russian Jewish girls. Sarah is fervently committed to growing Local 25, the shirtwaist workers local union, something that Luisa adamantly opposes. Sarah directly confronts the bosses’ regular practice of pitting the different ethnic groups against each other, such as recommending Angela for a sewing job. Sarah says that she doesn’t “like that the bosses always separate Jewish and Italian and American girls. They don’t want us to support one another, or talk to one another about what we want to change” (p. 48).

Hear My Sorrow is the only shirtwaist novel that acknowledges that the union, even Local 25, didn’t include the Italian girls or broader Italian community in its planning. When anti-union Luisa complains that “the leaders of this union haven’t even tried to talk to us; they don’t care about Italian girls,” Angela wonders “why there aren’t more Italians leading the union, especially if it is supposed to be for all workers” (p. 70). Many Italian characters worry that their parents won’t support the unions or striking, but in her historical note, Deborah Hopkinson reports that new research “points to a history of activism back in Italy by parents of the girls . . . as well as to a distrust of American unions such as the ILGWU in favor of more militant organizations such as the Industrial Workers of the World” (p. 172).

Several characters resort to scabbing at Triangle and are eventually killed in the tragic and entirely preventable fire. Hear My Sorrow, like Fire! (1992) and Uprising (2007), includes the memorial service held for the more than 140 dead at the Metropolitan Opera House where Rose Schneiderman bitterly urged unionization:

I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. And the only way is if there is a strong working-class movement. (p. 158)

Uprising (2007) is an extensive book that equally features Italian, Russian Jewish, and American workers. Unfortunately, one thing it doesn’t feature is dates, which are only given in the author’s note at the end. Yetta and Rahel are Jewish sisters who both work at Triangle and are both firmly committed to the union even though they’re clearly resentful of its male leadership. Yetta complains that “they’d never let a girl be in charge” and that “those big union men, they look at us like we’ve got fluff for brains” and say, “Now, now, you know it’s impossible to organize girls . . . . Girls can’t be depended on in a union” (p. 59).

Uprising (2007) is an extensive book that equally features Italian, Russian Jewish, and American workers. Unfortunately, one thing it doesn’t feature is dates, which are only given in the author’s note at the end. Yetta and Rahel are Jewish sisters who both work at Triangle and are both firmly committed to the union even though they’re clearly resentful of its male leadership. Yetta complains that “they’d never let a girl be in charge” and that “those big union men, they look at us like we’ve got fluff for brains” and say, “Now, now, you know it’s impossible to organize girls . . . . Girls can’t be depended on in a union” (p. 59).

Despite this, Yetta and others picketed before and during the Uprising of the 20,000. Bella, a 15-year-old recent Italian immigrant, is an unknowing Triangle scab. Because of language and cultural differences, she doesn’t know about the strike and doesn’t understand the picketing. She’s perplexed and horrified to see thugs, prostitutes, and police harass and beat picketers. Yetta and her friends discuss the result of the Uprising, which was that many smaller shops settled. Triangle eventually was willing to more or less meet many of the strikers demands ― except the most important one: recognition of the union which would result in a closed shop. Similar to the scene in Rosie (2003), when male union leaders urge strikers to accept Triangle’s offer, Yetta explains why union recognition and a closed shop is imperative:

It means that the factories will only hire union members. If they can hire anyone they want, why would they bother negotiating with us? . . . . Why would they bother following any of the rules they agree to if they can just hire nonunion workers and treat them however they want? (p. 177)

This crucial distinction needs to be clear, and Uprising is one of the only books that directly addresses the concept of a closed shop.

The Locket: Surviving the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (2008) is a largely forgettable book that begins after the 1909 strike but before the fire. Anya and 11-year-old Galena are Russian Jewish sisters who work at Triangle. The same brutal conditions faced by the workers, the fire, and the memorial detailed in Hear My Sorrow (2004) are also included. Leah blames Jewish immigrant parents’ “Old World ways” (p. 116) for preventing more workers from joining the union, which is a dubious comment given the extent to which Russian Jewish workers were involved in union organizing and membership.

Changes for Rebecca (2009) is a very brief “American Girls” historical fiction novel aimed at somewhat younger readers. Despite its inclusion in this category, Changes for Rebecca isn’t a shirtwaist book; it focuses on a strike at a coat factory in 1914. Very little specific information is given about the workers’ grievances, the strike itself, or its resolution, nor does it focus on a union (unions are only mentioned in the historical note at the end).Young Rebecca is at a picket line when police officers attack picketers. When a young female speaker is attacked, Rebecca attempts to speak to the crowd by reading aloud a letter that she’s written to the editor of a newspaper. I included this book because the beginnings of this strike are briefly mentioned in both Hear My Sorrow (2004) and Uprising (2007). Both books mention that the cloakmakers’ strike will be different from the Uprising in two fundamental ways: there will be a concerted effort to involve Italian workers in the strike planning, and that the strike is more likely to be successful because most of the workers are men. In Hear My Sorrow, Angela talks to Audenzio, a cloakmaker who says that “unlike Local 25 . . . [his union] has made an effort to involve Italians from the beginning” (p. 125). She reminds him that the “girls in our strike didn’t have much support from the men who are the union leaders” (p. 124). It’s quite galling, both for Angela in Hear My Sorrow and Yetta in Uprising, that the male union leaders “think they can win [the cloakmakers’ strike] because it’s all men” (p. 183).

Mine Novels

Interestingly, the two new mine novels, Up Molasses Mountain (2002) and Fire in the Hole (2004), are reminiscent of On Fire (1985) and Frankie (1997) in that they don’t take a clear stand on unions other than that union rank and file are likely violent thugs and union leadership are likely corrupt. The mine novels in particular — both the newer and older — are rife with bothsidesism and whataboutism, two terms that wouldn’t have been in common use at the times the books were published.

Fire in the Hole (2004) is a fictionalized account of the actual confrontation at the Bunker Hill mine in Wardner, Idaho, in 1899. Bunker Hill was not unionized, although many of the miners there were Western Federation of Miners (WFM) members. Very little in the novel explains the miners’ complaints for the strike that’s already begun before the novel opens. In fact, very little specific information is given at all — even including the date of the action or even the type of mine, which is only provided in an author’s note at the end. As the novel opens, teenage protagonist Mick is being pressured by Da to begin work in the mines, which will bring in more money than his work for a local pro-union newspaper. Da is a fervent union man, although little specifics are given. The main storyline in Fire centers on the “Dynamite Express,” a train seized by miners in Burke, ID, and its aftermath. As the train approached Wardner, it stopped repeatedly to pick up union miners and dynamite. Once the train reached Wardner, some of the dynamite was used to destroy expensive mining equipment at the Bunker Hill mine. Idaho governor, Frank Steunenberg, convinced President McKinley to send in federal troops who indiscriminately arrested men from Wardner and surrounding towns, saying that “the Constitution is void in the Coeur d’Alenes” (p. 69). As many as a thousand men were imprisoned in “the bullpen,” a makeshift prison.

Mick’s dad is one of the imprisoned. Because the family lives in company housing, they’re about to be evicted unless Mick scabs. Before being allowed to do this, Mick and the other scabs must use a Bible to “solemnly swear before God and those present [that they] will not participate in any union activity, nor join, nor seek to join any union so long as you are employed in the Coeur d’Alene mining district” (p. 124). After swearing, the scabs get to work. Young Mick and experienced miner, Hank, talk about the union and Hank insists that he’ll be a “union man” forever and that this is “temporary” (p. 136).

Unfortunately, the bulk of the novel focuses on Mick and his family’s attempt to break Da out of the bullpen, which they eventually do. Very little information about the pre-strike conditions are given. Also missing is much information about how the strike was resolved or the eventual fate of the men in the bullpen.

Up Molasses Mountain (2002) takes place in West Virginia in 1952, which is outside the timeframe of my original analysis. However, there are so few mine novels published in the last twenty years that I included it. West Virginia was the sight of some of the most violent mine union activity, from the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike in 1912 to the Matewan Massacre in 1920 to the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921. Molasses takes place barely thirty years later, but seems to be completely divorced from events in its fairly recent past. This story is about the last (fictional) non-union mine in West Virginia. The miners’ grievances are vague — maybe their coal is underweighed, maybe a foreman skimps on safety. This is offset by the fact that they are apparently paid more than miners at nearby union mines.

Early in the novel, Elizabeth, a teen protagonist and daughter of an anti-union miner, and her brother, Sterling, discuss unions and their father’s opposition to them, saying that “union men are nothing but trouble” (p. 28) and that they’re collecting an “armory” (p. 100). Sterling explains that a union might provide a retirement pension and implies that unions and pensions are “a new way of doing things” (p. 28) even though both had existed long before 1952. Elizabeth understands that her father would never join a union made up of men he refers to as “murdering thugs” ( p. 166) because he was “proud of his loyalty to the company,” and that joining would be a “betrayal” (p. 29). This sentiment isn’t contradicted by anything in the novel.

In a particularly egregious scene at the local church, the preacher, who is also a miner, says in a sermon that “we must obey the authority God has put over us. . . . We don’t need outsiders stirring up seeds of bitterness and discontentment with their murmurings against our brothers” (p. 40). The idea that unions are something brought in by outsiders is a common one. No miner in the congregation seems to object to the idea that mine owners apparently were set over miners in an act of divine authority.

As the union members come to town joined by pro-union miners in the town, Elizabeth’s sister informs her that “the union men are going to blow up the whole town if the miners don’t go on strike!” (p. 42). In addition to the assumption of violence, Elizabeth’s anti-union father explains his fundamental objection to unions, even after acknowledging that “long ago, unions did a lot of good” (p. 89). His astonishing view of organized labor is this:

I don’t begrudge a man for fighting if he thinks he’s being treated unfairly. But the union makes squeaky wheels out of men, turning them into people who do nothing but complain. I’ve lived long enough to know that there are some people who aren’t going to be happy with anything. The union makes men think they can’t change anything without them. I know men have more power together, but I don’t want to stand with a bunch of thugs. (p. 89)

The family’s grandmother recalls the Paint Creek strike (which had occurred 30 years before Molasses). She remembers how deadly the mines were and how poor the miners were and acknowledges that “there was nothing to do but strike, to fight for some way out of that life” (p. 44). She correctly mentions that Mother Jones was there helping to organize the miners and the families who’d been evicted from their company housing and admits that “the unions came down to help us families” (p. 44). Her story takes an inexplicable turn when she says that she visited Paint Creek years later and that it was “dried up” because the “union and machines” made people leave (p. 46). With no explanation, she claims that eventually “union bosses started looking an awful lot like the mine owners” (p. 46). Eventually, a strike is called, and there is some violence on both sides. We’re eventually told that the strike peters out and the union seems to wander off — no resolution on either side.

Both Fire in the Hole (2004) and Up Molasses Mountain (2002) present a picture of mine unions (both the WFM and the UMW) as violent — not as responding to violence. Neither book paints a clear picture of conditions in a mine or the legitimate grievances of miners.

Conclusion

As I read my original conclusion from twenty years ago, I’m very disappointed to say that almost nothing has changed. Only Hear My Sorrow (2004) gives clear and solid dates — an assumedly non-optional aspect of historical fiction. Several other novels (e.g., Fire in the Hole, 2004; Uprising, 2007) include dates in the authors’ notes at the end. This lack of historical specificity certainly lessens the impact of the novels and prevents young readers from being able to situate the information within any kind of larger historical context. One positive update involves one novel and the positive representation of the IWW, one of the most radical unions that isn’t included in any of the other novels. In the original twelve books, only Mother Jones appears. In the additional eight novels, IWW organizers, Joe Ettor, Big Bill Haywood, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, all appear briefly in Bread and Roses, Too (2006) about the Lawrence mill strike of 1912.

Books for young readers that address labor history trickled out for a while, but have become scarce, with almost none published in the last decade. Many major strikes, unions, and labor actions have yet to be written about for this audience.

In addition to some sources listed below that might be useful for teachers hoping to teach about unions and labor, I’d like to reiterate my earlier suggestion that students compare these historical novels to nonfiction and primary source materials. For older students, a critical reading supported by an open climate created by teachers would lead them to ask why these events happened and why they’ve been written this way in these novels.

Resources

Labor History and Labor Organizing booklist at Social Justice Books

Picture Books for Labor Day by What We Do All Day

Picture Books as a Springboard to Teaching about Labor Unions by Andrea S. Libresco, NCSS, 2015.

Works Cited

Anyon, J. (1979). Ideology and United States history textbooks. Harvard Education Review, 49, 361-386.

Armstrong, J. (2000). Theodore Roosevelt: Letters from a young coal miner. NY: Winslow Press.

Bader, B. (1993). East side story. New York: Silver Moon Press.

Bartoletti, S. C. (2000). A coal miner’s bride: The diary of Anetka Kaminska, Lattimer, Pennsylvania, 1896. NY: Scholastic.

Benson, S. P, Brier, S., & Rosenzweig, R. (1986). Introduction (pp. xv-xxiv). In S.P. Benson, S. Brier, & R. Rosenzweig’s Presenting the Past: Essays on History and the Public. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Colman, P. (1994). Mother Jones and the march of the mill children. Brookfield, CT: The Millbrook Press.

Dash, J. (1996). We shall not be moved: The women’s factory strike of 1909. NY: Scholastic.

Flagler, J.J. (1990). The labor movement in the United States. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications.

Goldin, B. D. (1992). Fire! The beginnings of the labor movement. New York: Viking.

Green, J. (1997). Why teach labor history? OAH Magazine of History, 11(2), 5-8.

Jones, J. S. (1997). Frankie. New York: Lodestar Books.

Josephson, J. P. (1997). Mother Jones: Fierce fighter for workers’ rights. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company.

Kornbluh, J. L. (ed.) (1988). Rebel voices: An IWW anthology. Chicago: Charles Kerr Publishing.

Lens, S. (1985). Strikemakers & strikebreakers. NY: Lodestar.

Lord, A. V. (1981). A spirit to ride the whirlwind. New York: Macmillan.

Matas, C. (2003). Rosie in New York City. Simon & Schuster.

Mays, L. (1982). The candle and the mirror. New York: Atheneum.

Meltzer, M. (1991). Bread—and roses: The struggle of American labor, 1865-1915. NY: Facts on File.

National Labor Relations Board. (2022, April 6). Union Election Petitions Increase 57% In First Half of Fiscal Year 2022.

Paterson, K. (1991). Lyddie. New York: Lodestar.

Perez, N. A. (1988). Breaker. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Rappaport, D. (1987). Trouble at the mines. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Junior Books.

Sachs, M. (1982). Call me Ruth. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Sebestyn, O. (1985). On fire. Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press.

Weiler, K. (1988). Women teaching for change: Gender, class, and power. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers, Inc.

Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and literature. London: Oxford University Press.

Zinn, H. (2003). A people’s history of the United States. HarperPerennial.

Deborah Overstreet is an associate professor of education at the University of Maine: Farmington.

Leave a Reply