Reviewed by Katie Seitz

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Book Author: Matt Dembicki

On November 1, 1950, Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, two Puerto Rican nationalists, attempted to assassinate President Truman. Their goal was to draw attention to the U.S. colonization of Puerto Rico and the repeated legal and military measures to deny Puerto Ricans self-determination. At the time, Truman was staying at Blair House while the White House underwent repairs. The two men converged on Blair House and, after a shootout that left Torresola and one policeman dead, Collazo was arrested and imprisoned.

District Comics: An Unconventional History of Washington, DC tells a slice of this story in “Truman,” by Art Haupt, Rafer Roberts, and Wendi Strang-Frost. In their version, three journalists on their way to Blair House happen upon the gunfight. In its aftermath, the young photographer is pressed into service to record the crime scene while his coworkers interview the police lieutenant. Truman leaves for his next engagement, saying “[a] president has to expect these sorts of things,” and all assembled marvel at his sang-froid.

“Truman” reveals some of District Comics’ major shortcomings. Like many other stories in the book, the line between fact and “creative liberties,” as editor Matt Dembicki puts it, is unclear. Were there actually journalists at the scene or were they inserted into the story as a framing device, along with their extensive dialogue? And if an effective framing device was needed, couldn’t the story have been better told from the perspective of Oscar Collazo, rather than the wooden, possibly fictional journalists and policemen who talk like soft parodies of 40’s gangsters? Whose DC history is being told, and why?

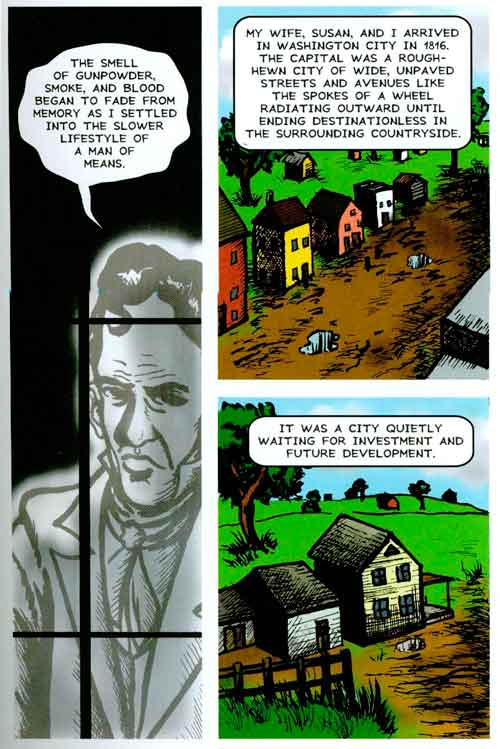

Questions like these plague much of the anthology, which contains 22 vignettes from as far back as the city’s founding and as recently as the 2008 Obama inauguration, each by different artists and writers. Dembicki’s stated goal is to tell lesser-known stories, those that “pop up during conversations with a longtime resident, through a community newspaper, or at a neighborhood barbecue.” However, given the stated parameters for inclusion, stories about Benjamin Banneker, the 1812 burning of the White House, Walt Whitman, and Ronald Reagan are relatively mainstream. The anthology is also highly unrepresentative of the city. Only five of the twenty-two entries tell the stories of people of color–all African American, all men. Only two entries tell the stories of women–both white. Of these two categories, one in each is narrated by a white man. There are oddly few women or people of color in the rest of the book, just the occasional compliant partner or face in a crowd.

Questions like these plague much of the anthology, which contains 22 vignettes from as far back as the city’s founding and as recently as the 2008 Obama inauguration, each by different artists and writers. Dembicki’s stated goal is to tell lesser-known stories, those that “pop up during conversations with a longtime resident, through a community newspaper, or at a neighborhood barbecue.” However, given the stated parameters for inclusion, stories about Benjamin Banneker, the 1812 burning of the White House, Walt Whitman, and Ronald Reagan are relatively mainstream. The anthology is also highly unrepresentative of the city. Only five of the twenty-two entries tell the stories of people of color–all African American, all men. Only two entries tell the stories of women–both white. Of these two categories, one in each is narrated by a white man. There are oddly few women or people of color in the rest of the book, just the occasional compliant partner or face in a crowd.

Few anthologies aspire to represent over 250 years of history, and comics about the District are thin on the ground. To create something this ambitious obviously took guts. Unfortunately, District Comics can kindly be described as uneven, with art and writing that range from exceptional to confusingly amateurish.

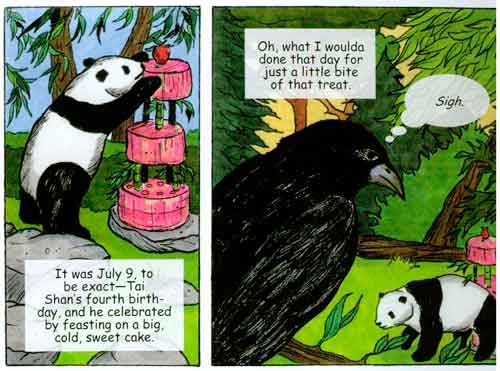

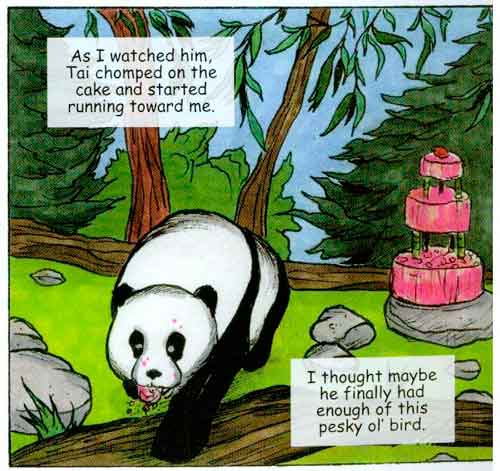

The best pieces are professionally rendered and competently written; the worst pieces may turn the reader off completely. Steve Loya’s “Crow and Panda,” an extended reminiscence about Tai Shan (the National Zoo’s former resident panda) by a friendly crow, manages to be both historically and artistically irrelevant. It is a slap in the face to pieces like Andrew Cohen’s well-drawn and executed “Dark Was the Night,” a tribute to outsider artist James Hampton, or Gregory Robison and Brooke A. Allen’s excellent “Impartial? Washington’s First Newspaper.” Some pieces of middling quality are made worse by the use of bad Photoshop effects or ineffective coloring.

The best pieces are professionally rendered and competently written; the worst pieces may turn the reader off completely. Steve Loya’s “Crow and Panda,” an extended reminiscence about Tai Shan (the National Zoo’s former resident panda) by a friendly crow, manages to be both historically and artistically irrelevant. It is a slap in the face to pieces like Andrew Cohen’s well-drawn and executed “Dark Was the Night,” a tribute to outsider artist James Hampton, or Gregory Robison and Brooke A. Allen’s excellent “Impartial? Washington’s First Newspaper.” Some pieces of middling quality are made worse by the use of bad Photoshop effects or ineffective coloring.

A comics anthology, by definition, provides little in the way of context, and Dembicki rightly uses the forwards of each piece to set the historical stage. However, none of the entries provides historical afterwords, and several end on a strange cliffhanger note reminiscent of serial superhero comics. This becomes infuriating, as in the otherwise brilliant “Karat,” about a man suspected of espionage by the FBI and CIA. His guilt hinges on a single voice recording of the spy, and he ends the piece by asking the reader, “[c]ould these guys tell his voice from mine?” Well? Could they? Since there is no “next month’s issue” to coerce the reader into buying, this serial-comics storytelling conceit seems unnecessary. A sentence or two appended by the authors could have provided a degree of closure, whether about Brian Kelley’s espionage charges or the fates of any of the various characters portrayed here.

A comics anthology, by definition, provides little in the way of context, and Dembicki rightly uses the forwards of each piece to set the historical stage. However, none of the entries provides historical afterwords, and several end on a strange cliffhanger note reminiscent of serial superhero comics. This becomes infuriating, as in the otherwise brilliant “Karat,” about a man suspected of espionage by the FBI and CIA. His guilt hinges on a single voice recording of the spy, and he ends the piece by asking the reader, “[c]ould these guys tell his voice from mine?” Well? Could they? Since there is no “next month’s issue” to coerce the reader into buying, this serial-comics storytelling conceit seems unnecessary. A sentence or two appended by the authors could have provided a degree of closure, whether about Brian Kelley’s espionage charges or the fates of any of the various characters portrayed here.

Given the range of the area’s untold stories, it is tempting to entirely reimagine the anthology. One vignette could tell the story of one of the Nacotchtank, the indigenous people who lived in what is now DC at the time Europeans arrived. Eyewitnesses to the Red Summer of 1919 and the 1968 riots could tell their stories. Narrators could be Chinese, Ashkenazi Jewish, and Salvadoran, from Anacostia or Alexandria, male, female, or non-binary-identified, free or enslaved. Instead, the anthology, for all its variety, displaces the voices of women and people of color. Once again, the reader walks away with the impression that white men make history, and that women and people of color are merely servants, wives, assistants, or assassins in their stories.

District Comics by Matt Dembicki

Published by Fulcrum Publishing on 2012

Pages: 253

ISBN: 9781555917517

SYNOPSIS: District Comics is a graphic anthology featuring lesser-known stories about Washington, DC, from its earliest days as a rustic settlement along the swampy banks of the Potomac to the modern-day metropolis. Spanning 1794?2009, District Comics stops along the way for a duel, a drink in the Senate's speakeasy, a look into the punk scene, and much more.

Featuring stories by:Scott O. Brown, award-winning man of comics and Harvey Award nominee

Chad Lambert, five-time Howard E. Day Memorial Prize finalist and writer for Kung Fu Panda and Megamind

Jim Ottaviani, creator of The New York Times bestseller Feynman

Leave a Reply