Social Justice Books draws inspiration from the work of the Council on Interracial Books for Children (CIBC) formed in 1965 with the objective “to promote a literature for children that better reflects the realities of a multicultural society.” The impetus to create the council came from Mississippi Freedom School teachers concerned by the racist portrayal of African Americans in school textbooks.

In 1966, the CIBC began publishing a book review called the Bulletin, which reviewed children’s books and materials, addressing negative stereotypes, biases, and historical inaccuracies. The goal was “to provide librarians and other educators with the perspectives of those our society has long oppressed — minorities, feminists, older people, disabled people, etc.” To do so most effectively, the CIBC engaged writers who were social activists and who were themselves part of the particular group represented in the book they were reviewing. [Note that the CIBC Bulletins are digitized and can be searched online at the University of Wisconsin.]

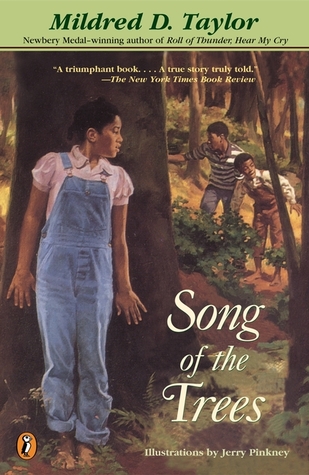

As it grew, CIBC developed as a resource center for culturally accurate and respectful books, teaching manuals, films, and lessons. Part of the obstacle to providing unbiased materials was that so few actually existed. In 1969, CIBC began an annual writing contest in an effort to get more African American authors published because they thought that publishers were more likely to accept a work if it had already won an award. Mildred Taylor and Walter Dean Myers both got their first book publications after winning the CIBC award. Over the years, the contest expanded to include prizes for Asian American, Chicano, Native American, and Puerto Rican writers.

One of the directors of the CIBC, Brad Chambers, provided an invaluable description of the history and purpose of the organization in this (ca.) 1983 interview with Noel Peattie of Sipapu. (Sipapu was a magazine “for libraries, collectors, and others interested in the alternative press, which includes small and ‘underground’ presses, Third World, dissent, feminist, peace, and all forms of indescribable publishing in general.”)

Interview with Brad Chambers about the Council on Interracial Books for Children

SIPAPU: Let’s start with the usual: birth and education, cultural background?

CHAMBERS: The education I received did nothing to promote an understanding of racism and sexism. Far from it: my formal education was designed to show the son of a white, relatively well-to-do family his proper place in the world. The texts I read at school (both here and in England) suggested that I, being white, was superior to people of color. I am lucky that the dinner table discussions at home contradicted most of this. I am also lucky that my father provided an antidote to the messages in the textbooks. He was a biologist, and before I had read any books on the subject, he had firmly debunked the myth of white superiority.

SIPAPU: Your political development: how your consciousness got raised?

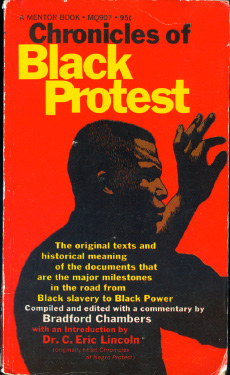

CHAMBERS: A major turning point for me came when I was collecting documents for a young people’s book on the civil rights movement, then taking place. The media reported on the events of the struggle, but did little to explain why they were taking place, and school textbooks were (and still are) equally deficient in putting these events in context, and relating them to history of struggles against oppression. To help fill the void, I complied Chronicles of Black Protest, which brought together historical documents of the struggle of Blacks for social justice. The book was quite successful. It received the 1969 Brotherhood Book award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews, and so it got into many great schools.

CHAMBERS: A major turning point for me came when I was collecting documents for a young people’s book on the civil rights movement, then taking place. The media reported on the events of the struggle, but did little to explain why they were taking place, and school textbooks were (and still are) equally deficient in putting these events in context, and relating them to history of struggles against oppression. To help fill the void, I complied Chronicles of Black Protest, which brought together historical documents of the struggle of Blacks for social justice. The book was quite successful. It received the 1969 Brotherhood Book award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews, and so it got into many great schools.

While researching Chronicles of Black Protest, I became more and more committed to racial struggle for equality. It was then that I first learned about the Council of Interracial Books for Children (CIBC). Two of my children were attending Downtown Community School (DCS) in New York City. I had volunteered to organize a project to bring children’s authors and editors to speak with the students about issues connected with children’s book publishing and I was also helping with the DCS annual award for children’s books that promoted human rights. DCS Principal Norma Studer, a high innovative educator, had started the award, and the contest had become a high point of the school year. (It was in connection with this award that Norman Studer, along with a number of librarians, editors and authors, had helped found CIBC in 1965). On one particularly hectic day in 1967, in the midst of demands from conservative parents to curtail the school’s scholarship program for minorities, Norman Studer asked if I would take his place that evening at a CIBC meeting. I have been with CIBC ever since.

When I joined, CIBC was judging the manuscripts submitted to its first Annual Contest for Unpublished Children’s Books by Negro Writers. (In those days “Negro” was still used). The contest was one way CIBC hoped to change what was then referred to as the “all-white world of children’s books” by encouraging the publication of Black authors. CIBC felt that publishers would be more likely to pick up a manuscript if it had won an award. And it was true that third world authors who had unsuccessfully made the rounds of publishers’ offices got their manuscripts published after they had won a CIBC award. Mildred Taylor’s manuscript, Song of the Trees, was rejected so many times that she nearly gave up. Once CIBC had given it an award in 1975, the book was published by Dial. The sequel, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, won the Newberry Medal. For some Blacks, the CIBC contest was the gateway to a new career: writing for children. Walter Dean Myers, now a well-recognized author, was working in the Brooklyn post office when he heard about the contest. He tried writing, submitted a manuscript, won the first CIBC award, and this led to a job as book editor in a major publishing house.

When I joined, CIBC was judging the manuscripts submitted to its first Annual Contest for Unpublished Children’s Books by Negro Writers. (In those days “Negro” was still used). The contest was one way CIBC hoped to change what was then referred to as the “all-white world of children’s books” by encouraging the publication of Black authors. CIBC felt that publishers would be more likely to pick up a manuscript if it had won an award. And it was true that third world authors who had unsuccessfully made the rounds of publishers’ offices got their manuscripts published after they had won a CIBC award. Mildred Taylor’s manuscript, Song of the Trees, was rejected so many times that she nearly gave up. Once CIBC had given it an award in 1975, the book was published by Dial. The sequel, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, won the Newberry Medal. For some Blacks, the CIBC contest was the gateway to a new career: writing for children. Walter Dean Myers, now a well-recognized author, was working in the Brooklyn post office when he heard about the contest. He tried writing, submitted a manuscript, won the first CIBC award, and this led to a job as book editor in a major publishing house.

Over the years, contest guidelines were developed to make sure that books were both anti-racist and anti-sexist, and the contest was expanded to include Asian Americans, Chicanos, Native American and Puerto Ricans. Prizes were awarded in each category. That the contest resulted in a number of beautifully written, highly acclaimed books would seem to contradict the charge from some quarters that CIBC guidelines inhibit a writer’s creative powers.

In addition to Mildred Taylor’s Newbury winner, several CIBC books have been runner-ups. The illustrations for for CIBC contest winner Margaret Musgrove’s From Ashanti to Zulu (Dial) won the 1977 Caldecott Medal.

Despite its achievements, the CIBC contest was always one of the best-kept secrets of the library world. The New York Times frequently reported the contest winners. The annual supplements of at least one encyclopedia and the Children’s Book Council’s awards and prizes regularly noted it, but the major library journals were silent about the contest throughout its ten-year existence. The contest continued until 1978 when they were no longer in a financial position to keep it going. The outlook for resuming it in the near future is dim since publishers have become less and less interested in books written by minority writers.

SIPAPU: CIBC, how it rose, how you got involved with it?

CHAMBERS: CIBC grew out of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. A teacher at one of the Mississippi Freedom Schools (begun as part of the voter registration drive and attended by many Black children) sent an SOS to his mother in New York, asking for print materials that Black children could identify with. His mother, the children’s book author Lilian Moore, searched for such materials but found none. This search spurred her to bring together, in 1965, a group of editors, writers, and librarians concerned about the lack of good children’s materials about Blacks. This group became CIBC. Author Franklin B. Folsom was the first chairman and civil rights lawyer Stanley Faulkner, the first treasurer.

The contest I mentioned earlier was one of the group’s first efforts to encourage the publication of books by and about minorities. Another was the publication of the CIBC Bulletin, which began in 1966 with a first issue of eight stapled pages. The Bulletin has certainly grown; now going into its 15th year, it is now a magazine running as many as 48 pages and published eight times a year.

The Bulletin is often controversial but consciousness raising. Its objective is to provide librarians and other educators with the perspectives of those our society has long oppressed — minorities, feminists, older people, disabled people, etc. Book reviews are written by members of the groups depicted, for we have found that the surest, most effective way to uncover bias and stereotypes is to ask for criticism from those who are struggling against their oppression. Who would have more sensitivity to bias and be more concerned about accurate, non-stereotypical presentations than members of the group portrayed? In addition to ethnic background, the reviewers we seek are activists working for social justice. Our approach caused not a little eyebrow-raising in the early years, but today the reviews are generally accepted as an extra and valid dimension of literary criticism. Bulletin reviews are now regularly selected for inclusion in two review annuals: Children’s Literature Review and Contemporary Criticism. H.W. Wilson’s Education Index has been indexing Bulletin articles for several years, and the Bulletin and other CIBC activities are regularly noted in the ALA Yearbook. A Bulletin article, “Whitewashing white racists: Junior scholastic and the KKK,” was selected as one of the “best contributions of to library literature” by Library Lit. II, the best of 1980 (Scarecrow Press, 1981).

Bulletin reviews are indeed critical, but there is much to criticize about our society, and once you start to recognize that children’s books reflect the biases of society, no detail is too small to ignore. Moreover, people are not always in agreement on what constitutes as a “small detail.” A dress making detail — a bow or a sash — while not an essential piece of clothing, may often alter the total effect. A small detail, indeed, may hold the key to a physician’s diagnosis. With this in mind, it is a critic’s reasonability when reviewing a book, not to overlook what may be regarded by as some as a “small detail,” but which may linger in some memories long after much of the book has been forgotten. This applies especially to children’s books portraying different cultures where attention to accuracy and authenticity is crucial.

The Bulletin is by no means all negative. Our reviewers find quite a few books to praise. This may come as a surprise to some, but the books that the Bulletin has recommended in recent years number into the hundreds.

We have also found that biased books make marvelous tools to teach children about bias, and rather than advocating the removal of such books, we urge that they be used in that manner. Once children gain insights into the nature and function of stereotypes, they are quite able on their own to spot stereotypes in books, on TV, and wherever bias occurs. Providing children with the skills to identify bias gives them a sort of defense, an antidote against the worst effects of bias. After all, we are not asking that children’s books remove women from the kitchen, but that they not limit women to that role. We are not asking that people of color be shown as saints, but rather that they not be restricted to subservient and stereotyped roles.

Eight years ago CIBC set up a resource center to assist educators in countering racism and sexism in school and society. Since then we have developed a large number of print and AV materials toward this objective. We publish, beside the Bulletin, books and teaching manuals. We create filmstrips and slide shows, develop lesson plans and school curricula, all with a consciousness-raising thrust. Some of these materials are being used by librarians, teachers, parents, church, and community leaders, in their localities or in workshops. Each item comes with a training manual and discussion guide.

A growing number of our materials are for use directly with students. We are particularly proud of “Violence, the Ku Klux Klan and the Struggle for Equality,” the first informational and instructional kit of its kind for use in junior and senior high schools. For its work in developing this material, CIBC just received the 1982 Human and Civil Rights Award from the National Education Association. But we have found that it is not just older students who can deal with the issues of social justice. Among our most enthusiastic supporters are fifth and sixth graders whose teachers have introduced them to the CIBC “winning ‘justice for all’” curriculum. At 10 and 11, children are particularly concerned with what is “fair” and “unfair,” and they become very much concerned about bias and discrimination. This six-week curriculum gives children insights into the institutional practices of discrimination, and the inequities that result from these practices. It has been very successful and is in use in 44 states and five foreign countries. We are just completing and AV resource which deals with issues of equity and social justice for first and second graders. And we are about to work on one for kindergarten. A free catalog of our CIBC materials comes from 1841 Broadway, New York, NY 10023.

SIPAPU: Your own outlook, on children’s books primarily: how important is it that books about minority groups, or books about scenes likely to involve minority groups (urban settings, certain rural areas) be written, or revised before publication, by members of the appropriate groups? Should an “establishment” (white, male, etc.) writer ask for revision, or just stay away from the subject entirely?

CHAMBERS: There is no question that any author has the right to write on any subject. However, when white writers chose to write children’s books about other cultures, especially those of people of color, they general short-change their young readers. There is a reason for this. Almost all whites grow up in a white cultural milieu and have only superficial experiences with people of color. They are also inundated with stereotypes and misinformation about minority groups in literature, textbooks, radio, TV. Then, too, there is no question that whites and people of color experience different realities, and that they perceive things differently. Therefore, it is very unlikely that white writers will adequately and accurately portray the cultural experiences and responses of minority groups. It is cultural arrogance to think otherwise. So, given a choice, then yes, it is preferable that books about minority groups be written by members of the group depicted. Writers from minority cultures can offer young white writers insights that they would otherwise not get, and offer young minority readers a validation of their lives that is so often missing from material by white writers. Let’s also recognize that while people of color in the U.S. must live in two cultures (the dominant white culture and their own), they generally remain as uninformed as whites about Third World cultures than their own. Ours is a very ethnocentric society.

That is not to say that white or majority white writers cannot write about minority cultures. They can make very important contributions by examining, for example, the dynamics of white racism. Surely, the chap at the right is doing this: let us give him the benefit of the infinitesimal doubt. It is simply that what they write will not be coming from the same perspective as a minority person. In a pluralistic society, where differences are respected, then, yes, intracultural writing would be much more effective, but it would not be easy; in such a society writers would be more likely to appreciate the difficulties.

You ask if an “establishment” author should request “revisions” from members of minority groups. I think writers should do their own revisions. On the other hand, I would certainly hope that any children’s book author who chooses to write of cultures other than his/her own, would seek input from members of the groups depicted. That is legitimate and necessary research. No one without intimate knowledge of a sport, or a particular science, would write about these subjects without getting some expert advice. Similarly, no editor would publish such children’s books without checking the content with an “expert.”

The way in which racial groups are depicted in children’s books is a major contributor to the way that white children think about other races, and to the way that minority children form their own self-image. Surely some “expert” input in this area would be all to the good. The same principle applies to the preparation of bibliographies. It does no good to merely put together lists of children’s books about a particular minority. Chances are better than even that those lists will contain not a few biased books. CIBC has urged librarians to develop a process to assure some minority input in the preparation of such bibliographies. For white librarians to invite minority input for the book selection process will not assure total accuracy, but it will cut down on a lot of unnecessary heartaches. Such a model book selection plan was featured in the CIBC Bulletin back in 1976 (“The Iowa plan — a due process for handling book challenges”, v. 7, no.7). The plan incorporates racism and sexism awareness training for librarians and outlines ways to bring minority input to communities of different populations.

SIRAPU: Should we actually launch a program of affirmative action in culture — i.e., publish more work by oppressed or disadvantaged people, or about them, and let the middle-class white males wait in the wings, so to speak? Or should we expand the pie to include opportunities for everyone?

CHAMBERS: About 20% of U.S. children are children of minorities but of the 2,000 children’s books published annually, roughly 1% are about these children. This denies minority children positive role models and a literature relevant to their lives. It is also a loss to white children who grow up ignorant and disrespectful of other people’s values and beliefs. That is why CIBC has long advocated affirmative action to see, out and publish talented Afro-American, Latino, Native American, and Asian-American writers and artists.

Yes, we should definitely work to expand the pie so that greater opportunities will be available for everyone, so that there will be more diversity and so that no group will be excluded. But enlarging the pie without altering the proportional share of its slices will be inequitable also. The reality is that the white writers are — and always will be — favored over minority writers. This does not mean that they have any inherent “right” to be published at the expense of non-white writers. I suggest that it is more pertinent to look at the “right to publish” that is currently being denied to minority writers. They are disproportionately under-represented, and children’s literature is the poorer for it — as we all are.

SIPAPU: If we should get more money to minority publishers, emphasize the disadvantaged to the disadvantage of more favored groups, how do we deal with the charge of the “Moral Mojarity” types that claim they are the insulted and injured, that their values are flouted, and they demand as much consideration as anyone else?

CHAMBERS: I assume you are talking about textbooks rather than children’s trade books, since these are what Mel and Norma Gabler of Texas, and other-so-called Moral Majority (MM) types are complaining about. Phyllis Schafly, incidentally, has called on the right to make school textbooks one of its four top priorities.

As many research studies show, minorities, women and numerous other groups have long been stereotyped in textbooks. Their history and perspective have been distorted or omitted, their concerns have been ignored or ridiculed. Serious scholarships, as well as a concern for social justice, necessitates that efforts be made to provide more accurate, more inclusive textbooks. It is not a question of emphasizing one group to the disadvantage of others. Instead, it is a question of representing a diversity of viewpoints of groups who have been discriminated against and whose voices have not generally been heard. The Moral Majority seeks to make books even more exclusive, as regards alternative viewpoints, than they are today. Groups like CIBC, on the other hand, seek to make them much more inclusive. We don’t mind including the Moral Majority view — as long as other viewpoints are there also. In that respect the Moral Majority people have no cause to feel “insulted and injured.”

The Moral Majority is not really calling for equal space but for total space. They insist that U.S. policies and leaders not be criticized. And their demands have already had an alarming impact on the adoption requirements of Texas, a key state today in determining textbook content. For example, the 1980 Texas criteria require that textbooks “present positive aspects of America and its heritage . . . shall not contain material which services to undermine authority . . . shall not encourage lifestyles deviating from generally accepted stands of society.” The Moral Majority is also demanding that all students, not just their own children, be taught absolute standards of right and wrong. They are pressuring for textbooks that permit but one right answer to questions and that disallow critical thinking and value judgments. Therefore, it is totally impossible to make the Moral Majority types happy, and, at the same time, educate a responsible citizenry. Should the colonists have worried because King George felt “insulted and injured”?

A small digression here concerning school textbooks: These books carry the official sanction of the educational establishment and are required reading by law. A case could be made that textbooks that omit or distort the histories of women and minorities violate the equal protection guarantees of the 14th Amendment.

SIPAPU: To what extent does the quest for fairness impair not only general freedom, including the freedom to be wrong, but (when pursued by librarians) expose them, to the charge of no longer being “neutral”?

CHAMBERS: Far from impeding freedom, the quest for fairness enhances it. What better way do librarians have to achieve intellectual freedom than by offering perspectives that have traditionally been left out? Almost all books that are published — and therefore the overwhelming number of books in library collections — are written from a middle and upper-class white perspective and they generally reflect the sexist values of our society no matter what the author’s gender. On issues of racism and sexism, there is no conceivable way to achieve a neutral collection, since the collections are so imbalanced to begin with, and anti-racist, anti-sexist books are so terribly limited in number. In view of this, the charge that a quest for fairness will somehow interfere with the librarians’ position for neutrality is a false charge.

Many librarians seriously question the concept of neutrality in book selection. To begin with, lets recognize that the existing book selection process — which begins with what gets published — is not truly neutral. One apparently innocuous example: the romance books for pre-teenagers in which young girls denote themselves to finding and getting Mr. Right. It’s no accident that books like these (they have been called training bras for the Harlequins) were the rage of the 1950s, that time of general conforms and raging sexism. (And it is interesting that they are being published and popularized again now, when there is a backlash to the feminist movement). Publishers who churn these books out, and the few librarians who endorse them, are not making a neutral choice: they are endorsing some very specific messages.

For children’s librarians to become aware of the messages contained in books and to carefully consider the number of books that endorse and perpetuate racism, sexism, and other anti-human values, is simply another way to clarify the selection process, not de-neutralize it. Put another way, the act of selection involves judgment about what is valuable and vital, and sensitization to minority and feminist consciousness one way, among many, of informing that judgment. I do wish that more schools of library science would show an interest in message contest and introduce sensitizing courses that will enable children’s librarians of the future to analyze content as well as literary values. We are encouraged, however, that children’s literature professors, and reading and language arts instructors, at college and universities are definitely showing more concern.

SIPAPU: What is the largest currently ignored group which you see as needing adequate favorable treatment in children’s books?

CHAMBERS: Many groups are still omitted from children’s books, but it would be unfair to single out one group most in need of “adequate” representation. Some believe that book publishers met their responsibility to minorities by responding to the pressures of the Civil Rights Movement and publishing books on Black themes. In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, children’s book publishers did come out with quite a few such books, some good, many more far from adequate. Publishers were reacting to Federal funds that enabled libraries to purchase such books as much as they were to pressures from the Civil Rights Movement. “Black is gold” they use to say.

Once the Federal funds stopped, books on Black themes became fewer and fewer. As for other minorities, the situation is bleaker still. We are just completing a ten-year update of a special 1972 Bulletin on children’s books about Puerto Ricans. The high point for these books was 1972, when a grand total of 18 children’s books on Puerto Rican themes was published. A graph, which will appear in the next Bulletin, tells what happened subsequently. By 1974, there was a precipitous drop to three books, then a slight increase over the next couple of years to seven books in 1977, followed by a steadily downward trend to zero books in 1980.

The group that is most represented is, ironically the most consistently misrepresented. There are more children’s books about Native Americans than about all other minority groups put together, but with a handful of notable exceptions, these books reinforce traditional stereotypes. Despite all the new awareness of the oppression of Native Americans, the average children’s books continue to depict them as painted, whooping “savages,” or as “exotics,” not as people living and continuing to be oppressed in today’s world. That is why Mary Gloyne Byler, a Native American critic of children’s literature, has said, “There are too many children’s books about American Indians.”

SIPAPU: Bilingualism: help to smaller children or handicap in adjusting to an inevitably English-speaking society?

CHAMBERS: There really is no substance to the charge that non-English speaking children will be at a disadvantage unless they stop pushing their native language at home and start speaking only English. Numerous studies now show that bilingual children who develop proficiency in both their native language and a second language have intellectual and academic advantages over monolingual children. The important thing is that children learn the cognitive skills on the language that is spoke at home, whatever language that is. Once they develop cognitive skills, around grade 3 they can readily transfer those skills to English. In what is known as transitional bilingual education, children are taught reading and other cognitive skills in their native language, while studying English as a second language. Sometime between the third and the sixth grades, the native language is dropped and the medium of instruction becomes English. In maintenance bilingual education, the medium of instruction is divided about equally, once the cognitive skills are learned. Some subjects are taught in English, others in the native language.

An outstanding model of maintenance bilingual education is Rock Point (Navajo) school in Chinle, Arizona. Before the program was introduced in 1971, there had been intensive efforts to begin teaching Navajo children English in kindergarten, but by the sixth grade they were two years behind U.S. norms in reading skills. A bilingual program introduced Navajo as the medium of instruction from kindergarten through sixth grade and for about 50% of the time there after. Instruction in English was introduced in the middle of the second grade. By the end of the sixth grade, the children were performing somewhat above U.S. grade norms in English reading.

A big problem in our society is that any language other than English is considered somehow inferior. The opposite holds true in some other countries, where different languages are shown equal respect. There are those who believe that proficiency in more than one language improves the speaker’s ability to reason and consider alternatives. A lot of confusion surrounds bilingual education, and I would like to recommend to SIPAPU readers a toll-free number they can obtain factual information about this. 800-336-4560 is the number of the National Clearinghouse of Bilingual Education in Rosslyn, Virginia.

SIPAPU: To what extend are we in the mess we are in, because while “majority rules” in this country, the minority has few, if any, rights other than what the majority is willing to grant the minority?

CHAMBERS: I believe the mess we are all in goes well beyond majority vs minority, whites vs people of color. It is the value system of our society — with values like acquisitiveness, competitiveness, aggressiveness — that are at the root of the mess. These anti-human values must be changed before we can hope to attain race and sex equity and social justice. This explains why, for example, the CIBC Bulletin has broadened the scope of its concerns to consider the societal values reflected in children’s books and other learning materials. We believe that in reflecting the values of society, children’s learning materials will perpetuate them, and we want to see those values changed. I agree with the conclusion of an article you wrote about CIBC, which appeared in Sipapu some years ago (v. 8, no.1 consecutive issue no. 15, January 1977; p.16-20) that children’s books cannot change society (our p.19). That would be expecting far too much. But children’s books can provide content that questions traditional assumption and role models, and so help achieve a more equitable just society.

Now, to return to your question about an oppressive majority. Your question implies that we have majority rule in this country. I disagree with that. Political and economic power is concentrated in the hands of a relatively few well-to-do white men, and they benefit very materially from this society’s value system. Even though all white people benefit, in some degree, from white skin privilege in a racist society, the majority of white people are actually harmed by the present system’s values. Unfortunately, few whites recognize this.

In my view, those oppressed by the present white male establishment constitute the majority of people in this country. When you consider the number of women of all colors, male minorities, poor white males, disabled people, gay men and lesbians, older people, working people — that’s a huge majority indeed. When these groups come to see the interrelatedness of their particular oppressions and work together toward common goals — whites seriously confronting racism, males seriously confronting sexism — social change will assuredly follow. Of course, that is what consciousness raising is all about.

SIPAPU: Where do we go from here? Is the outlook bleakly totalitarian, or are we raising more consciousness than ever before?

CHAMBERS: Globally and nationally, it is possible to see both hopeful and terrifying trends. I recall reading about a panel of historians and philosophers — Toynbee Sartre, Russell, among them— who were brought together in the 1960s to consider the state of the world. They observed that Western nations were becoming increasingly militaristic with ever-mounting military budgets, and they concluded that by the year 2000, Western society would be essentially totalitarian. However, between then and today, political consciousness has been rising at an accelerated pace. Blacks sparked the process with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. All kinds of movements since then have broadened people’s consciousness, and many more people are becoming aware of the essentially oppressive structure of our society. The struggle that these movements provoke is, of course, the important thing. As Frederick Douglass said, “If there is no struggle, there is no progress.” It is when these struggling movements begin to understand each other’s issues and form coalitions that there will be a possibility for turning around the thrust toward totalitarianism. I think the special issue of the CIBC Bulletin, which we have just published, is pertinent to this discussion. It reports on militarism and education and draws links between issues of racism and sexism and our society’s strong militaristic bent. We hope to reach people active in a range of equity struggles and to help make connections between their particular struggles and the anti-nuclear/disarmament movement. The patriarchal, racist militarists have the power, but they are not invincible if the rest of us manage to get ourselves together.