By Amy Rothschild, pre-school teacher and Teaching for Change volunteer

I teach in a preschool program at a public school, and while my teaching team and I have ample freedom to follow the children’s interests in our planning, our school does place a high value on the teaching of nursery rhymes. Nursery rhymes are to early childhood curricula what Frost and Poe are to high school—we may come to love them, but we teach them first out of obligation to a “common cultural knowledge.”

But what exactly is—or should become—common cultural knowledge for students from diverse linguistic, racial, and national backgrounds? At my school we stock books showing a wide range of families and realities, many from Teaching for Change’s selections. How hard could it be, I wondered, to find a little space on the shelf for nursery rhymes, considering they would be a part, and not the whole, of what we read and learn?

Some nursery rhymes, like Ten Little Indians, reinforce negative stereotypes and roles and teachers should avoid them. Others are more mundane—folks baking pies, sitting on tuffets—hard to understand, but not unconscionable. I assumed that while nursery rhymes have an Anglo-Saxon origin, there is no reason that only white people can be depicted wishing upon a star. But practically every felt-board piece, website, puzzle, and book I found preserved the link of nursery rhymes to whiteness and Eurocentrism. White Little Bo Peep counting her white sheep, white Mary bringing her white lamb to her all-white school.

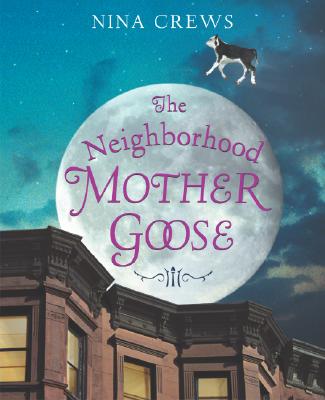

Enter Nina Crews’ The Neighborhood Mother Goose. Crews spent three years choosing settings in her Brooklyn neighborhood to stage child-appropriate nursery rhymes, and the result is a phenomenally engaging book that I am proud to show my students. One four year-old African-American boy called out at the page for Hey Diddle Diddle: “Hey, that boy looks like me when I was a baby!” Such moments of seeing oneself reflected positively in the world are vital for children--they need to see themselves both as agents of change and in more everyday moments, like those that Crews presents.

Of course, in addition to contemporary illustrations paired with Anglo-Saxon nursery rhymes, we need to offer our children chances to learn rhymes and poems from many languages and traditions. Teachers who talk about nursery rhymes extol their benefits for teaching children rhyme and awareness of the sounds in words, and for increasing their oral language—overlooking that these are the benefits of short texts in general, not the exclusive rights of Jack Horner, “good boy” though he thinks he is.

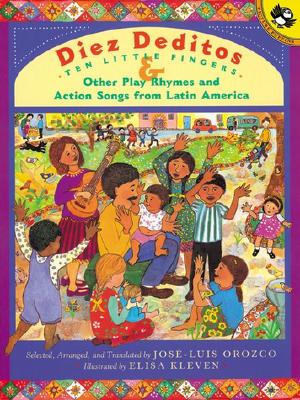

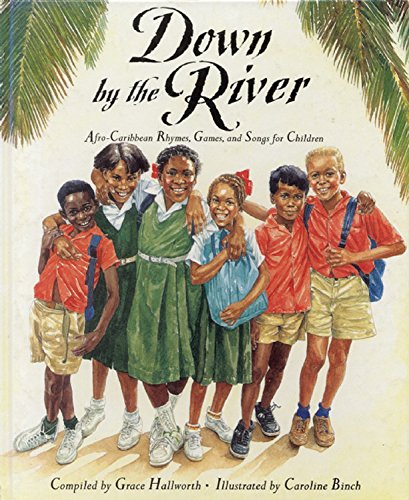

In that spirit, the list, and we welcome your suggestions. First, a note: The list presents a wide variety of songs and poems for young children. Too often, teachers fall into the trap of presenting the “normal” nursery rhymes and the “other” or alternative one. That framing is inaccurate and fails to take into account the growth and concurrent development of distinct literary traditions. Each of these works is a complete and self-sustaining reality.