Reviewed by Paige Pagan

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Book Author: Alejandra Domenzain

For All Para Todos takes children on Flor and her father’s journey of crossing the Mexico-United States border and the injustices they face as undocumented immigrants in a nation that is heralded as one united para todos. Growing up, television serves as a window for Flor to witness life on “that side” where children have “oh so much stuff!” (p. 1), unlike her own family who never have enough. When the land that Flor and her father sustain themselves on becomes decimated and they don’t have the resources to bring it back to life, Flor’s father knows that crossing the border is the only way for them to survive. For Flor, this means an exciting plane ride into the land para todos where toys will be waiting for her, food from all places, and people with different faces. However, the journey is nothing like what she’s envisioned. Through deserts and rain they arrive at the border to be given papers with big red X’s on them. Flor goes on a process of discovery as all of her and her father’s hopes and dreams in this new land are jeopardized because of their undocumented immigrant status. She comes to the hardest realization of all: that in this land, “justice for all” means “justice for some” (p. 30) where immigrants are left out. Because of this experience, Flor resolves to use her voice to advocate for immigrant and worker rights and encourages others — documented and undocumented alike — to do the same.

For All Para Todos brings attention to the underrepresentation of immigrants, underscoring their particular struggles of social and economic disparity, cultural and lifestyle differences, the fear and threat of deportation, isolation and exclusion, the pressure to succeed, and the risk of exercising your voice to fight for equality. Being bilingual and utilizing a lyrical rhyme scheme makes the book accessible and appealing to all children. The book also inspires children to ask important questions, as Flor does, about who is being represented and accepted and who is being erased and rejected by the systems and policies held in society. The book motivates children to use their voices for social change.

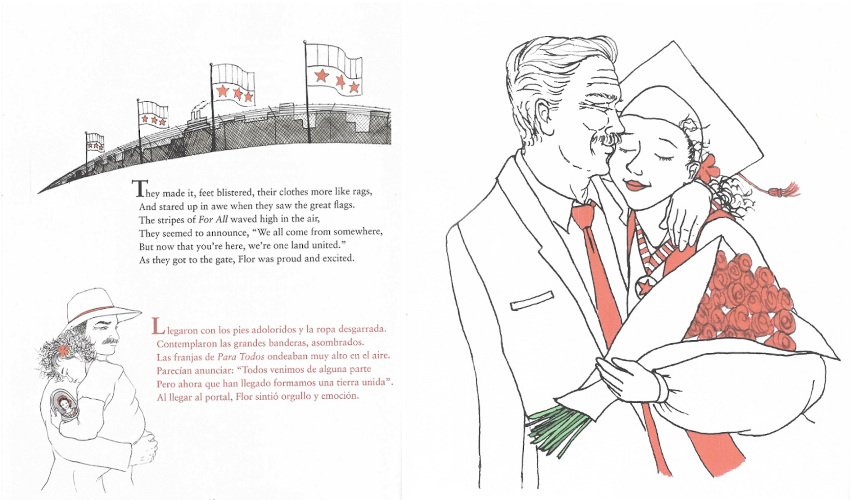

For All Para Todos begins with the divide between Mexico and the United States, which is heightened as Flor and her father eventually make it over the border and the documented versus undocumented distinction reigns. Flor’s mental image of the United States corresponds to what she sees on television, a romanticized nation of hopeful tomorrows and happy endings where “no one was hungry and the law made things right” (p. 4). Flor’s dad envisions the United States to be a land of equal opportunity where “all hard workers are given a chance, fair and square” (p. 8). Although both have high expectations of what the land para todos will hold for them, they are saddened by the inability to return home where Flor’s mother is buried after losing her life to illness acquired from hard labor in a factory. Domenzain writes this loss of family and home that immigrants face in a way that children can understand as Flor questions who will pull out the weeds and bring fresh flowers to her mother’s grave when they’re gone. The pain of leaving continues to be felt as readers follow Flor and her father on their perilous trek to the border to be given papers with red X’s on them, denying legal entry. Flor wonders what they have done wrong because X’s in school are always bad. Here is where both Flor and her father’s initial perceptions of the land para todos begins to change.

Life in the land para todos proves to be a challenge for both Flor, who is ostracized in school, and her father, who is driven to exhaustion from working day and night. Students bully Flor for her Spanish name and her struggle to grasp English and American culture. Flor longs to find community with kids who “came from far away, too” (p. 14) and questions if coming to this new place was a big mistake. She finds comfort in Ms. Soto, the language arts teacher, who tells her that she has a story similar to Flor’s and so do others in school. Ms. Soto encourages Flor to find her voice through writing and to share her story in the school paper. When Flor’s story becomes one that many students find relation with and are grateful for, Flor is optimistic that things will get better. But when she goes home to her empty, run-down apartment, she is once again doubtful. When her father comes home at night from work, she asks, “Why don’t you have money if you work without stopping?” Her dad explains that as an undocumented immigrant, the only work available is to toil in the fields without complaint or risk being jailed and deported.

Flor sees the sacrifice that her single-father has made in order for Flor to get an education so that she can have a better life. Flor understands that she must do more than write stories, and that it’s safer to keep silent and blend in. She studies hard for her entrance exams so that eventually she can have a fair job, unlike that of her father, in order to help mothers who are ill like hers was and to provide for her father. Loh puts Flor’s dreams in a heartwarming illustration of her in a cap and gown in her father’s embrace, which can be compared to an earlier illustration of her father carrying her on the brink of collapse to the border. These illustrations outline the adversity they have faced and the hopeful reward. Here readers feel the pressure of immigrant children (and first-generation children of immigrants) to succeed in order to secure the brighter future their parents worked so hard for them to obtain.

Being rejected from a prominent school due to her undocumented status, despite her getting a top score, sparks a fight in her to advocate for immigrant and worker rights. Motivated by the need to “convince them [citizens who can legally vote and exercise their political rights] to make a new rule, to work without fear and be let into school” (p. 31), she interviews immigrants all over town, writing their stories. Flor makes it on television to amplify immigrant voices and publicize the truth. Even though Flor had to learn that “For All wasn’t all it should be” (p. 34), she believed in collectivity as the path toward achieving justice, what the country should be about. Children see that united, a group with goals that they believe in can change unfair laws.

The takeaway of this book aligns with the critical race theoretical principle of critiquing liberalism and therefore questioning who is being left out of the laws and policies in place. This also relates to the concept of structural determinism, the idea that our system is ill-equipped to redress certain wrongs, including those against immigrants. While the book charts political participation and activism as a concrete way forward for immigrants, one step further would be to acknowledge that in a nation that’s based on legal precedents which have upheld racism as normal, antiracist efforts extend beyond law and policy. This book is highly recommended.

Paige Pagan is a Social Justice Books Program Specialist at Teaching for Change.

For All by Alejandra Domenzain

Published by Hard Ball Press on March 15, 2021

Genres: Bilingual, Immigration and Emigration, Latinx

Pages: 54

Reading Level: Grade K, Grades 1-2

ISBN: 9781734493870

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Publisher's Synopsis: Flor and her Dad make the dangerous journey from their poor country to a land called For All/Para Todos. As Dad works long hours picking fruit in the fields for little pay, they soon learn that immigrants are not welcome. As Flor grows up, she learns that her story, like the story of so many migrants, needs to be told. She picks up her green pen and writes from the heart about her life in this beautifully illustrated bilingual children's book, written in musical rhyme. A timely children's story about the hopes and dreams of immigrants and the harsh realities of life in a new country, For All/Para Todos is a tone poem for families to enjoy together.

Leave a Reply