Reviewed by Jenice L. View

Review Source: Teaching for Change

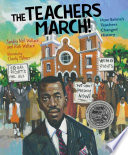

Book Author: Sandra Neil Wallace, Rich Wallace

Overall, this book is very well researched and cited. It centers Black people, their strategic thinking, and their agency at a time when the national story of the Black freedom movement was being complicated by heightened white supremacist violence, rising resistance to the Vietnam War, Cold War politics, and increasing decolonization efforts around the world. These were all issues that were quite familiar to the members of the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL), founded more than 40 years prior to the teachers’ march and comprised of middle class African Americans in Selma. The book also highlights youth activism that was supported by teacher complicity.

There are examples of lyrical phrasing that make reading the book aloud a pleasure: “the white section of town where the red dirt road turned to pavement;” “the somebody somebodies of the community. College educated. Shiny leather shoes. Suits and Sunday brooches seven days a week. No group like that had marched for freedom before.”

The book makes the case — that seems to be true — that except for the Silent Parade of 1917 in New York and the 1963 March on Washington, there had not been a march for the freedom of Black people prior to the Teachers March of Selma in 1965. It is a powerful story that is well told.

Unlike many children’s books, this one includes the names of many people in the Selma community, including women and children, who were essential to the outcome of the story. And yet there are some ways that teachers might want to complicate the story by introducing some of the facts the authors chose to put in the author’s note and timeline. For example, the book falls into the trap — common to children’s literature — of focusing attention on a single hero or heroine, in this case, Reverend Frederick Douglas (F.D.) Reese. While he was the president of the DCVL at the time of the teachers march, he was not the founder, nor should the book ignore the long leadership of Amelia Boynton, an activist for women’s suffrage in childhood, an activist for Black voting rights since the 1930s, a candidate for statewide elected office, the wife of the organization’s second president in 1936, and a member of the steering committee in 1965.

A central theme of the book is the powerful strategy of having the Selma Black teachers march for voting rights because of the high regard in which they were held by the Black community of Selma. Yet, it does three things that are problematic. First, by stating that, “No group of leaders had risked their jobs before by marching” — it plays into the trope that sharecroppers — who also risked their jobs — were not leaders. Second, it diminishes the quiet and powerful activism of Selma’s Black middle class for the 40 years leading up to the Teachers March. Third, it erases any mention of the students who courageously walked out of class and marched before the teachers did. These young people are missing from the story and in the afterword, their activism is placed incorrectly in the timeline.

While the text acknowledges that a judge issued an injunction in July 1964 making illegal the gathering of two or more people at a time to talk about voter registration or civil rights, it fails to mention the 32 Black Selma teachers who had previously applied to vote at the courthouse in 1963 and who were fired by the all-white school board. If some people in Selma whispered that the teachers “did not have the courage” to march, they likely also understood that Black teachers were respected leaders and middle class, who engaged in respectability politics, in behind-the-scenes activism, and in self-preservation.

Another children’s book device is to identify a single villain, in this case Sheriff Clark. The book hints at the economics of segregated schooling in 1964: Sheriff Clark needed to reinforce segregation to keep his job, Rev. Reese needed his job at his school that was segregated, Clark worked for the superintendent and for the system of segregation that would perish if the superintendent fired all of the Black teachers. Clark represents a system of oppression and the first act of the newly registered Black voters is to vote him out of office. But a teacher might want to explain how that single act was not sufficient for changing local politics or dismantling an entire system of racism.

Finally, the text states, “Americans noticed. They wondered why respectable citizens in suits and dresses, and school kids carrying books, were jailed. The president of the United States noticed. He pushed for a new voting rights law. That summer of 1965, the Voting Rights Act passed. It made certain that nobody had to take a test just to vote.” This is a much-too-glib statement about the origin of the Voting Rights Act, and especially about the circumstances in Selma in the first eight months of 1965. Jimmie Lee Jackson’s murder, Bloody Sunday, the murders of two white supporters of Black voting rights (Viola Liuzzo and Rev. James Reeb), the continuing direct action of Black Selma citizens and others around the South were additional factors to motivate President Johnson to push Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act.

Young students are able to understand that a single hero and a single villain and a single president and a single vote may be necessary to initiate change, but that it takes an entire community of committed people, over time, to make the change stick.

The Teachers March! by Sandra Neil Wallace, Rich Wallace

Published by Astra Publishing House on September 29, 2020

Genres: Civil Rights Movement

Pages: 44

Reading Level: Grades 1-2, Grades 3-5

ISBN: 9781629794525

Review Source: Teaching for Change

Publisher's Review: FOUR STARRED REVIEWS! A Booklist Editor's Choice An Orbis Pictus Honor Book

"An alarmingly relevant book that mirrors current events." — Kirkus Reviews, starred review

Demonstrating the power of protest and standing up for a just cause, here is an exciting tribute to the educators who participated in the 1965 Selma Teachers' March.

Reverend F.D. Reese was a leader of the Voting Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama. As a teacher and principal, he recognized that his colleagues were viewed with great respect in the city. Could he convince them to risk their jobs — and perhaps their lives — by organizing a teachers-only march to the county courthouse to demand their right to vote? On January 22, 1965, the Black teachers left their classrooms and did just that, with Reverend Reese leading the way. Noted nonfiction authors Sandra Neil Wallace and Rich Wallace conducted the last interviews with Reverend Reese before his death in 2018 and interviewed several teachers and their family members in order to tell this story, which is especially important today.

Leave a Reply