By Amy Rothschild

By Amy Rothschild

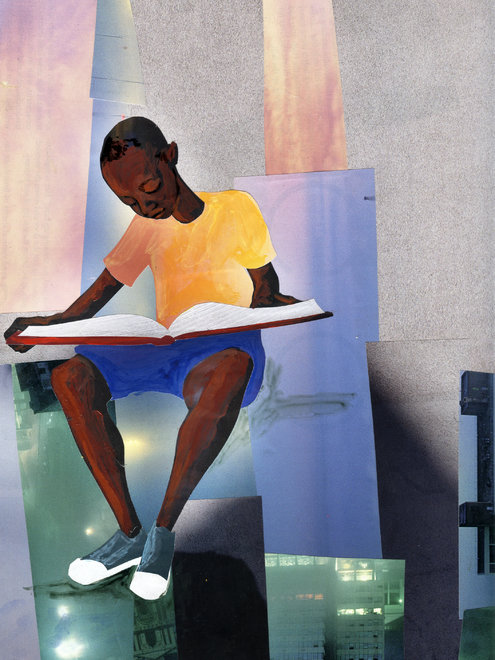

In March, Walter Dean Myers and his son Christopher Myers brought national attention to a question often asked by frustrated parents, teachers, librarians, and youth: where are the people of color in children’s books? The two authors wrote must-read op-eds featured on the front page of the New York Times Sunday Review. Both testified to the role that books play in mirroring, validating, and imagining the human experience, and the loss incurred for all of us when children of color are left out. These ideas, masterfully written and worth frequent rebroadcasting, are not new.

In fact, Walter Dean Myers wrote a similar op-ed about the invisibility of children of color in children’s literature–in 1986. It’s worth a read, because it anchors this problem as a worsening one, and also identifies efforts that contributed to a fleeting time of commercial success for authors of color.

In his 1986 op-ed, “I Actually Thought We Would Revolutionize the Industry,” Myers wrote:

The 1960’s promised a new way of seeing black people. First, and by far most important, we were in the public consciousness. Angry black faces stared out from our television sets, commanded the front pages of our tabloids. We were news, and what is news is marketable. To underscore the market the Federal Government was pumping money into schools and libraries under various poverty titles. By the end of the 60’s the publishing industry was talking seriously about the need for books for blacks.

Myers described the 1960’s as a turning point. He outlined how publishers turned to white authors already in the industry to write stories to satisfy the demand for books featuring children of color, until a progressive coalition organized to disrupt that practice:

In 1966 a group of concerned writers, teachers, editors, illustrators and parents formed what was to be called the Council on Interracial Books for Children. The council demanded that the publishing industry publish more material by black authors. The industry claimed that there were simply no black authors interested in writing for children. To counter this claim the council sponsored a contest, offering a prize of $500, for black writers. The response was overwhelming. It was the first time I had actually been solicited to write something about my own experience.

Myers was not the only author to get his start this way: peers like Mildred Taylor and Eloise Greenfield participated, and they, like Myers, are still among widely read black authors.

It bears emphasis that it was not simply a contest, but also a context that contributed to this bloom.

And when the context changed, no contest alone could remedy it:

[In the late 60’s] things were looking up. I believed that my children and their contemporaries would not only escape the demeaning images I had experienced but would have strong, positive images as well. … Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.

Myers points to Nixon’s dissolution of Great Society program and the subsequent decrease in library funding as a major factor in a return to a status quo in which publishers insisted books by and about people of color wouldn’t sell.

As a consequence, Myers wrote in 1986:

Walking through the aisles at this year’s American Library Association meeting in New York City was, for me, a sobering and disheartening experience. Were black writers suddenly incapable of writing well? Of course not, but we were perceived as no longer being able to sell well.

What has happened in the intervening decades since 1986?

In 2014, Myers writes with still greater urgency and desperation:

Today when about 40% of public school students nationwide are black and Latino, the disparity of representation is even more egregious. In the middle of the night I ask myself if anyone really cares.

Indeed people do care–though not organized into a single coalition, people are speaking out. In 2009, Zetta Elliott, award-winning author of books for youth, wrote “Something Like An Open Letter to Children’s Book Publishers.” Awards and databases have been established by activists with a focus on major gaps and mis-representations, not only of black authors and characters but of other underrepresented groups as well. These include groups such as Africa Access, the Amèricas Awards, American Indians in Children’s Literature, and more. The Cooperative Children’s Book Center makes the invisibility of books by and about authors of color visible with its annual count. Lee & Low Books maintains a blog tracking these trends. There is a Birthday Party Pledge to get multicultural books as gifts for children. The NY Times feature of the Myers’ articles reflects a growing national awareness and recognition of crisis in children’s book publishing.

Of course, as Myers’ 1986 editorial makes clear, changes in children’s book publishing happen in tandem with broader social and political movements. Do we see signs of such a movement crystallizing in our day? Will a renewed civil rights movement focus on mass incarceration? On rising economic inequality? Will it be framed in terms of race, or wealth? Right now, it is too soon to tell.

But as Myers makes clear in 2014, as he did in 1986, any vital social movement that reimagines the role of people of color in our world must also provide young minds a way to see this change reflected. And that will happen when people demand that children can see themselves reflected in the pages of children’s books.

Amy Rothschild is an early childhood educator with experience teaching pre-K in public and independent schools. She is a fellow at Teaching for Change.